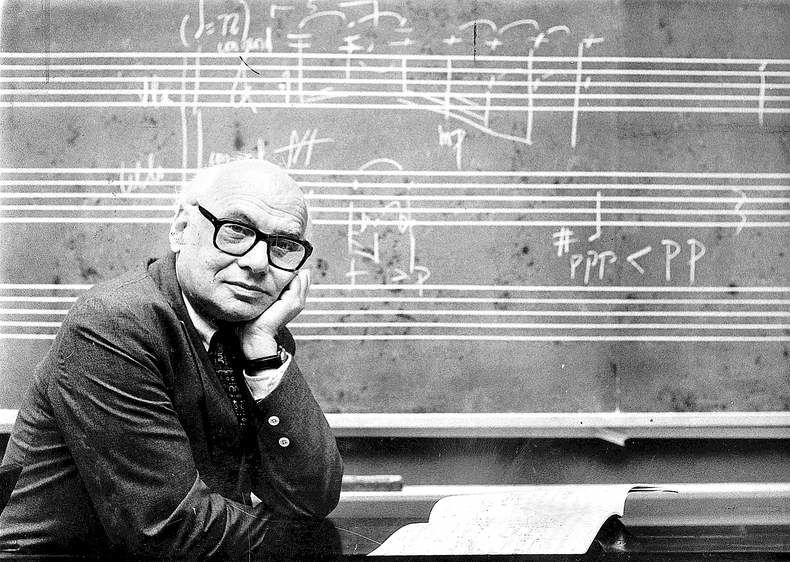

Milton Babbitt, composer who challenged listeners

Published 4:00 am Monday, February 7, 2011

- Milton Babbitt, seen here in 1982, was an influential composer, theorist and teacher who wrote music that was intensely rational and for many listeners impenetrably abstruse. He died Jan. 29 at the age of 94.

Milton Babbitt, a composer who used his knack for mathematics to create a modern musical language that was elegantly complex, fearlessly dissonant and so dense that even critics sometimes struggled to explain its importance, died Jan. 29 at a hospital in Princeton, N.J. He was 94. The cause of death was not reported.

For six decades, Babbitt wrote orchestral pieces and music for chamber groups and vocalists, including pioneering arrangements for the electric synthesizer.

His work, praised by New York Times music critic Anthony Tommasini for its “mercurial contrasts of mood, impishly jagged lines, constantly shifting surface motion, elegant colors and fine nuances of texture,” profoundly influenced younger musicians such as Philip Glass and Steve Reich. One of Babbitt’s early students was the future Broadway composer Stephen Sondheim.

“I am his maverick, his one student who went into the popular arts armed with all his serious artillery,” Sondheim once said.

Babbitt received a MacArthur Foundation grant and, in 1982, a special Pulitzer citation for his lifetime achievement as a “distinguished and seminal American composer.”

His compositions built upon the groundbreaking work of Austrian-born composer Arnold Schoenberg, who had devised a new way to write music in the early 20th century.

Schoenberg’s “serial” method — in which a composer arranges 12 notes in an order that is revisited and manipulated throughout the piece — marked a dramatic break with the musical theory that undergirds much of Western classical music. Babbitt was among the first to extend Schoenberg’s serialism to elements including rhythm and timbre.

The result was music guided by a set of rules that made for pieces both challenging to perform and difficult — for many listeners — to love.

“It has long been fashionable to say that music like this grows in comprehensibility if we will only give it our time and attention, but I doubt it,” Times critic Bernard Holland wrote about the 1998 Carnegie Hall premiere of Babbitt’s “Second Piano Concerto.”

Babbitt was unbothered by the fact that his music was, as he put it, “nonpopular.”

In a controversial 1958 essay — “Who Cares If You Listen?” — he argued that audiences shouldn’t expect to enjoy or understand cutting-edge music, just as lay people don’t expect to comprehend physicists’ discussions about high-level science.

The essay turned Babbitt into a symbol of what many thought was modern music’s cerebral snobbery. He was unapologetic.

“The real arrogance comes not from composers, but from people in the audience who presume to know without having earned the right to know,” he said in 1982.

“Illiterate musical audiences,” he later said, “have no idea what music has been, so how can they have any idea of what music is or could be?”

Milton Byron Babbitt was born May 10, 1916, in Philadelphia.

He grew up in Jackson, Miss., where one of his childhood friends was novelist Eudora Welty, whose family lived a few doors down.

Babbitt began studying violin at 4. “By the time I was 8,” he told the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, “I realized the violin had no social future, so I switched to sax and clarinet.”

Within a few years, he was playing with touring New Orleans jazz bands and arranging pop songs.

He studied math at the University of Pennsylvania until his uncle, a pianist, introduced him to Schoenberg’s compositions — “pieces that I couldn’t really believe were music,” Babbitt later said. He was fascinated and transferred to New York University to study music.

Babbitt’s music was technically difficult to play, and he was drawn to synthesizers as a way to reduce his reliance on performers’ skills. In 1959, he became one of the first directors of the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, home to one of the most advanced synthesizers of the time.

Among his best known pieces for the synthesizer is “Philomel,” written in 1964 for soprano Bethany Beardslee.

Beardslee sang the part of a woman transformed into a nightingale, her live performance delivered against a backdrop of her own recorded voice. The synthesized sounds “served as a chorus to the soloist, commenting, repeating and giving breathing space,” wrote Times critic Howard Klein. “The effect of the work was startlingly original.”