CIA losing intel war to private sector

Published 5:00 am Thursday, April 14, 2011

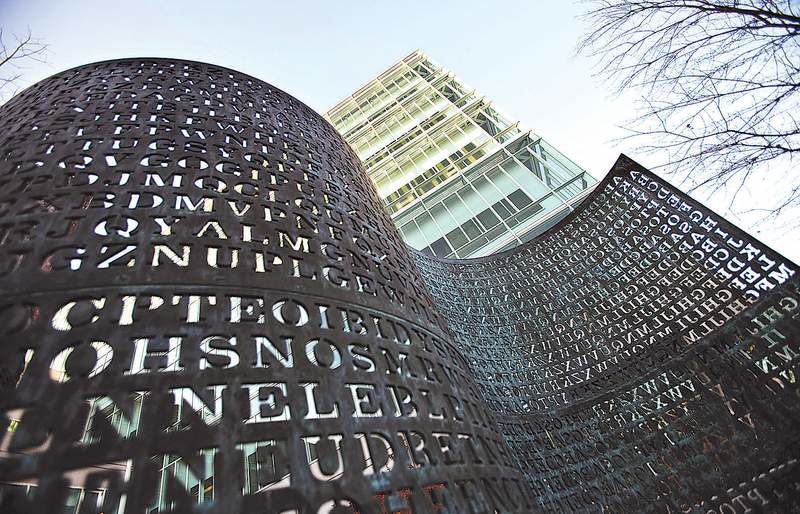

- The mysterious “Kryptos” sculpture in the courtyard of CIA headquarters in Washington. From 1990 through 1996, Congress had slashed the intelligence community's budget every year, and from 1996 through 2000, it effectively left the budget flat.

In the decade since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, private intelligence firms and security consultants have peeled away veterans from the top reaches of the CIA, hiring scores of longtime officers in large part to gain access to the burgeoning world of intelligence contracting.

More than 90 of the agency’s upper-level managers have left for the private sector in the past 10 years, according to data compiled by The Washington Post. In addition to three directors, the CIA has lost four of its deputy directors for operations, three directors of its counterterrorism center and all five of the division chiefs who were in place the day of the Sept. 11 attacks and responsible for monitoring terrorism and instability across the world.

In many quarters in Washington, government officials decamp for the private sector as a matter of course. Defense consultancies routinely hire generals retiring from the Pentagon; the city’s lobbying firms are stacked with former members of Congress and administration officials.

But the wave of departures from the CIA has marked an end to a decades-old culture of discretion and restraint in which retired officers, by and large, stayed out of the intelligence business. It has also raised questions about the impact of the losses incurred by the agency. Veteran officers leave with a wealth of institutional knowledge, extensive personal contacts and an understanding of world affairs afforded only to those working at the nation’s preeminent repository of intelligence.

Among the CIA’s losses to the private sector have been top subject matter experts including Stephen Kappes, who served as the agency’s top spy in Moscow and who helped negotiate Libya’s disarmament in 2003; Henry Crumpton, who was one of the CIA’s first officers in Afghanistan after the Sept. 11 attacks; and Cofer Black, the director of the agency’s counterterrorism center on Sept. 11.

The exodus into the private sector has been driven by an explosion in intelligence contracting. As part of its Top Secret America investigation, The Washington Post estimated that out of 854,000 people with top-secret clearances, 265,000 are contractors. Thirty percent of the workforce in the intelligence agencies is made up of contractors.

Those contractors do everything from assessing security risks to analyzing intelligence to providing “risk mitigation” services in foreign countries.

“Since 9/11, the demographics of the agency have been out of whack. A number of people left the agency earlier than you would think, and you had a large influx of younger people,” said Robert Grenier, a 27-year agency veteran who is now chairman of ERG Partners, a boutique investment bank specializing in the intelligence industry. “The average experience of an officer now is much lower than it has been traditionally, and that has its effects on the agency.”

For private firms seeking to tap into the lucrative industry of intelligence contracting, the value of having agency officers on the payroll is hard to overstate. And although the agency pays its top managers large sums — the most senior officers make nearly $180,000 annually — private firms are generally able to pay more.

This report is based on interviews with more than a dozen current and former CIA officials. The Post compiled its list of more than 90 upper-level managers by identifying agency personnel who left for the private sector after serving as directors, deputy directors or chiefs of the CIA’s various divisions, as well as other members of the leadership of the Directorate of Operations, now known as the National Clandestine Service.

CIA spokesman George Little said that “any suggestion that there isn’t world-class, senior expertise at the CIA is flat wrong.”

“Retirement is a fact of professional life,” Little said, “and the CIA has created strong mechanisms to assist our officers as they explore opportunities after retirement and to retain their knowledge before they go.”

The bulk of the agency’s losses to the private sector came roughly from 2002 through 2007, as business with intelligence contractors spiked. In fiscal 2010, a senior U.S. official said, attrition rates at the CIA were at an all-time low.

Some of the officials quoted for this report spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivities involved in discussing the agency’s inner workings. Few of them cited problems at the agency as their reason for leaving. Rather, they said, the choice was often financially driven.

Intelligence demand

Years of intelligence reforms found the CIA unprepared for the events that followed the Sept. 11 attacks. From 1990 through 1996, Congress had slashed the intelligence community’s budget every year, and from 1996 through 2000, it effectively left the budget flat.

Suddenly, with a demand for better intelligence, the agency needed more bodies. It needed people to deploy to Afghanistan. It needed top-level linguists. It needed interrogators. Insiders and outsiders quickly concluded that the CIA needed contractors.

Richard “Hollis” Helms, a longtime overseas officer and former head of the agency’s European division, founded Abraxas Corp. in the days after the attacks. Helms identified the areas in which the agency needed the most help and began aggressively recruiting current and former intelligence professionals.

Those professionals included mid-level analysts from the Directorate of Intelligence. But they also included top brass such as Rod Smith, a former chief of the agency’s Special Activities Division, and Fred Turco, one of the original architects of the CIA’s counterterrorism center and the former chief of external operations. Meredith Woodruff, one of the agency’s most senior female operatives, signed on to Abraxas in 2006.

“Hollis is brilliant; he realized there was a huge market out there to exploit. He printed money for a while — hired tons of CIA staffers and doubled their salary. He was the first agency guy to figure it all out,” said one former chief of station, the term for the top CIA officer at a U.S. Embassy. “You would see people leave the CIA on a Friday and come back on Monday in the same job but working for Abraxas.”

Barry McManus, an agency veteran, was among those who saw the promise of Abraxas.

McManus had worked for the CIA his entire career, with the exception of a few years on the D.C. police force. He started out as a bodyguard for CIA Director William Casey, then climbed through the ranks, eventually doing work in more than 130 countries. By 1993, he had become the CIA’s chief operations polygraph examiner and interrogator, responsible for interviewing high-level terrorism suspects and others in the process of interrogation.

But when he turned 50 in 2003 and found himself eligible for retirement, McManus said, he realized he wanted to do something else.

Now, as vice president of training and education at Abraxas, he spends much of his time training others in the law enforcement and intelligence world. Among his contracts is one with the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, which hired him to lead a four-day class that covers an introduction to terrorism.

According to government contracting documents, in a separate four-day period in 2006, he made nearly $40,000 for leading a seminar for immigration officers in “detecting deception and eliciting responses.” A year later, he secured a $238,000 contract to perform guest lectures. Pretty soon, more contracts began rolling in.

McManus said he is well-compensated for his work at Abraxas. One of his first big purchases in post-agency life: a black Maserati GranTurismo, which retails for $160,000.

Slowing the brain drain

At the agency, Director Leon Panetta has helped slow the hemorrhaging of talent. But this year he has seen his top three leaders leave the agency. Collectively, they represented more than 75 years of institutional knowledge and operations talent.

One former official said the loss of so many insiders has taken a toll on those connected to the agency.

“Honestly, it’s painful to see, and it’s not in the national interest to see so many men and women at the peak of their experience walk out of the agency at the age of 52 or 53,” the former official said. “The agency would be well served to implement stronger incentives to encourage people to stay.”

Bob Wallace, a 32-year agency veteran who now runs Artemus Consulting Group in McLean, Va., suggested the departures from the agency reflect more than the draw of a big salary outside government. Rather, he said, some veterans who have risen to the management level are leaving for a much more mundane reason: bureaucracy.

“People tire of meetings,” Wallace said. “Eventually, they decide they want to jump to the private sector so they can be back on the street again — doing what they love.”