Unforgettable Chinatown

Published 4:00 am Sunday, November 16, 2008

- Unforgettable Chinatown

SAN FRANCISCO — Order up a plate of braised sea cucumber with duck feet. Make an incense offering to Tin How at a Taoist shrine. Visit a herbalist’s shop to obtain raw ginseng root or dried snakeskin to cure what ails you. Go shopping for carved jade or a sleek, side-slit cheongsam (a traditional dress), and don’t forget to tell the clerk, “Xie xie ni.” That’s Chinese for “Thank you.”

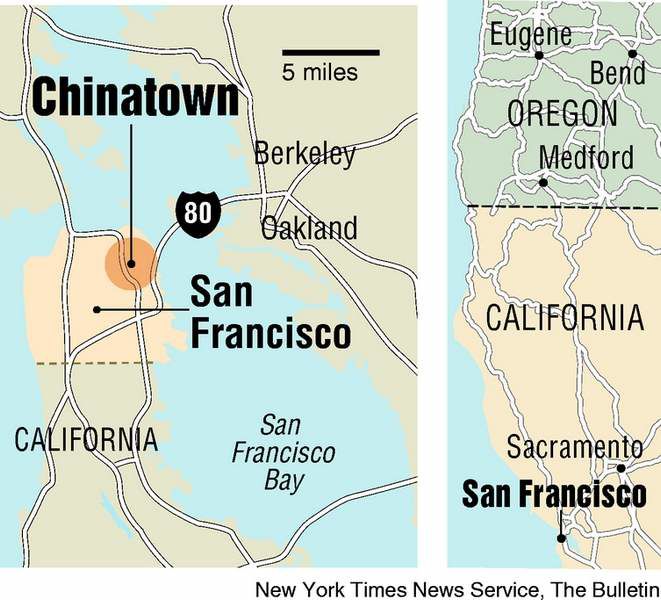

It’s all a mere day’s drive from Central Oregon in San Francisco.

An estimated 30,000 people, more than live in Redmond, make their homes in the 24 square blocks of San Francisco’s Chinatown, the largest such community in the United States after New York’s Chinatown. A majority of residents are either recent immigrants or first-generation Americans who still speak their native Cantonese or Mandarin dialect.

Whenever I visit San Francisco, I make certain that I dawdle for a few hours in Chinatown. Only three blocks from Union Square, located on the east-facing slope of Nob Hill and right on a principal cable-car line, it lies at the heart of one of the world’s most touristic cities — and it offers a window into a world far more exotic than California itself.

A little history

San Francisco got its start in Chinatown. What today is Portsmouth Square, at the heart of Chinatown, was once the central plaza of the Anglo-Mexican settlement of Yerba Buena. Capt. John Montgomery raised the American flag here for the first time in 1846 and claimed the soon-to-be-renamed community as U.S. territory; two years later, the square was the site of the announcement of the discovery of gold in the nearby Sierra foothills. Through the gold rush era, it was a bustling hub of activity.

Today, Portsmouth Square is a much quieter place. Elderly men congregate at tables to play cards or Chinese chess and to socialize. Giggling schoolchildren dash through on their way to and from classes. Monuments to 19th-century author Robert Louis Stevenson and to Chinese killed in the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing stand on opposite sides of the square.

It was the California Gold Rush that first inspired thousands of Chinese to come to this corner of the world. Most were Cantonese from Guangzhou and Hong Kong, in southern China; because they intended to return to their homeland after striking it rich, few made an effort to learn English or embrace Western culture. But deteriorating social conditions under China’s ruling Manchu Dynasty led most to remain in North America.

By 1870, according to the Chinese Historical Society of America, more than 63,000 Chinese were living in the United States. Their single-largest community was focused along Sacramento Street, a block south of Portsmouth Square. Outside of San Francisco, they were rail workers (helping to build the first transcontinental railroad) and farm laborers (especially in the San Joaquin Valley); within the city, they pioneered the local fishing industry and opened small businesses such as mercantile stores and laundries.

An economic depression in 1872 led to a wave of rioting against Chinese, who were willing to work for lower wages than other Americans. In 1882, the federal Chinese Exclusion Act forbade Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States. (Merchants and their families were still allowed admission.) This act effectively left thousands of Chinese bachelors without mail-order brides, the Chinese Historical Society reports, and Chinatown evolved into a rowdy, male-dominated community.

By the late 19th century, it had become a notorious center of vice. Gambling halls, brothels and opium dens were rife. Immigrants joined “tongs,” protective associations based upon family name or home city in China. Tong wars erupted between factions seeking to control underworld profits. Eventually, leaders of the most powerful tongs formed a confederation known as the Chinese Six Companies, which remains an important social force in Chinatown today. Its colorful Stockton Street headquarters is among the city’s most elaborate buildings.

The Chinese Exclusion Act wasn’t repealed until 1943. A new wave of arrivals from the Far East followed, especially since the 1960s. Today, even though many younger, wealthier and better-educated Chinese live elsewhere in the San Francisco Bay Area, they often return to Chinatown to shop and mingle in the restaurants, markets and bookstores.

Tourist gateway

Like most visitors, I most often walk into Chinatown at Chinatown Gate, which arches over Grant Avenue on the north side of Bush Street. Built in 1970 by Clayton Lee, a local Chinese-American, to represent a traditional Chinese village entrance, the ornate gateway has ceramic dragons and carp on its roof to usher in good fortune.

The eight blocks of Grant Avenue that stretch north from here to Broadway comprise the main visitor thoroughfare through Chinatown. What Rodgers and Hammerstein observed half a century ago in “Flower Drum Song” remains much the same today. Colorful painted facades and balconies, pagoda-like towers and curved-tile rooflines give the neighborhood an exotic flavor.

Retail outlets sell a seemingly endless selection of souvenirs, some of them very inexpensive (like fans and key chains), others priced in the thousands of dollars. Jewelry, silk fabrics and intricate carvings from semiprecious rock are very popular.

One block up Grant Avenue, and a stutter-step to the right (east) on Pine Street, is St. Mary’s Square. Chinatown’s largest park is anchored by a statue of Sun Yat-sen, who was widely regarded as the father of Chinese democracy. Sun raised money in San Francisco to support the successful 1911 revolution against China’s Manchu Dynasty; his republican government is still in power on the island of Taiwan.

Just across California Street, at the corner of Grant Avenue, stands Old St. Mary’s Cathedral. California’s largest building when it was constructed in 1854 as the first seat of the Archdiocese of San Francisco, it was gutted by fire following the great earthquake of 1906, but its thick stone walls remained intact. Classical noon-hour concerts are frequently presented here. At any time, it’s worth a visit to see the photographs of late-1800s Chinatown displayed in the vestibule.

Turn left at Sacramento Street and climb a short half-block before turning right on narrow Waverly Place. Sometimes called the “Street of Painted Balconies” for its elaborate chinoiserie, it’s an alley full of sounds: Mahjong tiles clicking behind closed doors, the beat of drums as young tong members practice for festivals and parades.

Three buildings have temples on their upper (third and fourth) floors, and non-Chinese visitors are welcome so long as they show respect for the faiths and make small donations to the temples’ upkeep. The Tin How Temple, established in 1852 (and in its present building since 1911), is Chinatown’s oldest Taoist shrine; it is devoted to Tin How, the “Queen of Heaven” and protector of seafarers. The Norras Temple was the first purely Buddhist temple in the mainland U.S. when it opened in 1960; you can learn your fortune by shaking a container of bamboo sticks until one falls loose.

For Chinatown visitors who don’t want to ascend stairs or elevators to reach lonely temples, the most accessible is the Ma-Tsu Temple. Located on Beckett Street, a narrow alley east of Grant Avenue between Jackson Street and Pacific Avenue, it has a street-front entrance and all the glitter a casual temple-goer might need. On its altar is the “Queen of Heaven,” flanked by a pair of all-seeing, all-hearing attendants.

Authentic flavors

Climb another half-block uphill from Waverly Place to Stockton Street if you want to see the locals’ Chinatown. Not prettified for tourism, Stockton is jam-packed with ma-and-pa markets and shoppers. Roast duck and chickens hang by their necks in store windows. Barbecued pigs stare back at passers-by. Fresh fish markets have you pointing and wondering at what depths such strange-looking creatures might be found.

Heaps of freshly picked vegetables and fruit, much of it unfamiliar to supermarket shoppers, inspire intense but amiable bargaining between Chinese matrons and the shop owners.

At the Red Blossom Tea Company, Peter Luong carries more than 100 bulk teas, but he takes time to explain to visitors what to look for in a quality tea, whether green, black or oolong. “Each is as unique as wine, depending upon their region, style, soil type, harvest time, even the tradition and the brewing temperature (ideally between 190 and 195 degrees),” Luong said.

Throughout Chinatown you might be fortunate to hear the erhu, a traditional two-stringed musical instrument, being played like a violin by street performers. One of the most adept is a barber named Jun Yu, who has a shop in Ross Alley, a long block uphill from the Ma-Tsu Temple between Grant and Stockton, Jackson and Washington streets. Jun, who had a small part in the 2006 movie “The Pursuit of Happyness,” sets up a folding chair outside his tiny shop and gives impromptu concerts on request.

If strange musical instruments intrigue you, you’ll want to drop by the fabulous Clarion Music Center at Sacramento Street and Waverly Place. This is my favorite place to explore a world of unfamiliar music-makers, to hear beautiful new sounds from the 21-string gu zheng and the percussive ku lin tang, and talk to the people who produce them. A regular concert series is offered.

My favorite reason to visit Chinatown, however, is the food. My guideline for choosing a Chinatown restaurant is always: Are there more Asians eating here than Caucasians? If so, I feel reassured that I’m going to find more authentic tastes.

There are a great many different types of Chinese cuisine, and all of them can be found in Chinatown. Western palates are often most attuned to Cantonese foods, the more delicate seafood- and vegetable-rich plates of Hong Kong and southeastern China. Dim sum is a great introduction to traditional Cantonese flavors; large restaurants like the Imperial Palace and Empress of China offer dim sum lunches and weekend brunches for very reasonable prices. Bite-size steamed dumplings most often stuffed with shrimp, pork and vegetables, dim sum are priced according to the number of plates ordered. It doesn’t take a lot to fill up.

Hearty Mandarin and zesty Szechuan cuisines are well-known in the West. Hunanese is gaining popularity in the U.S., but such traditions as Fujian, Shandong and Huaiyang are virtually unknown outside of Asia.

If you’ve got an adventuresome streak but are a little worried about trying something new by yourself, I suggest you seek out Shirley Fong-Torres. This effervescent San Francisco native, who has conducted Wok Wiz Chinatown Tours since 1977, freely shares her traditional culture with interested tourists. I last joined her three-hour walking tour about a year ago (the cost was $40), and I still consider it one of the most worthwhile experiences I’ve had in San Francisco.