Roasting hazelnuts brings out flavor

Published 4:00 am Tuesday, November 6, 2012

- Ryan BrenneckeThe Bulletin

Did you know that the Willamette Valley and surrounding region grows 99.9 percent of the nation’s domestic hazelnut crop? It began at the turn of the 20th century with George Dorris, who jumped in with both feet. And that, of course, is a story all unto itself — how the hazelnut industry in Oregon began.

An even earlier grower was Ferd Groner. In 1880, at the age of 17, Groner helped his family build a grand Victorian-style house, one brick at a time. The historic estate still stands where Scholls Ferry Road and River Road intersect about 20 miles southwest of Portland.

After taking over the family business at age 28, when his father died, Groner soon built a farming empire around hay and walnuts. Somewhere along the way he also put in a hazelnut orchard, which grew to 200 acres. It wasn’t until 1943, when he was 80, that Groner decided he needed some help with the orchard. His ad in The Oregonian was answered by Andrew Loughridge, who had a wife and infant son to support and needed the work. To the questions posed byGroner, “Do you smoke? Do you drink?” Loughridge was able to answer in the negative. Groner took a shine to him and even invited the family to move into living quarters on the lower level of his brick mansion.

The Loughridge family lived in the main house for about a year before moving to another house on the estate. A few short years after that, Groner died. In his will, he bequeathed half of the hazelnut orchard — 100 acres! — toLoughridge. And so, for the next 60 years, Loughridge grew hazelnuts.

It was a life that suited a man with such a strong work ethic, with the consistency of its year-round demands. His barn-like red nut dryer, with its iconic cupola, drew customers from near and far. Others came to Loughridge Farm to buy his nuts. And after Loughridge filled up their bags and weighed them, he always topped off the purchase with a few extras — just in case there were some bad ones.

Up to the age of 89, he was still farming the entire orchard on his own, with only one hired hand. Then he leased out all but 5 acres, which he kept working. In November of 2005, at the age of 94, Loughridge suffered a debilitating stroke. That previous October, however, he had participated in the harvest one last time. He’d raked the end rows in the orchard, run the sweeper and even driven the tractor pulling the harvester that picked up the wind-rowed nuts.

Before his death, he was told that the price for nuts had hit a new high, $1 a pound. His eyes lit up: “I’ll have to tell the bank to get a bigger box to put my money in.”

You’ll begin to notice lots of markets rejoicing in the fact that the harvest has just been completed, and they can now boast “new crop” hazelnuts. Here are a few ways to relish their goodness.

Roasting hazelnuts

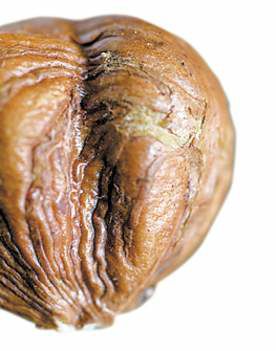

Three things happen when you roast a hazelnut: it gets more flavorful, it blushes from the inside and it takes on a pleasing crunch. So you definitely want to roast them in most cases. Another way to look at it is that roasting almost always improves how hazelnuts perform in a given recipe.

This is simple stuff, roasting hazelnuts. There is no absolute right way to do it. The pendulum swings from “low-and-slow” all the way over to “high-and-fast.” I tend to go for the middle range, 350 degrees. At that temperature you have quite a bit of control over the outcome. A medium roast only takes about 15 to 20 minutes. At higher temperatures, things move a bit quicker, and it’s easy to overshoot your desired endpoint. When you begin to smell the delicious toasty aroma, it’s time to start checking the roasting progress. The longer you roast hazelnuts, the richer their flavor. You have to decide how deep of a roast you want based on how you’re planning on using them.

Light roast: The skins have cracked on the majority of the nuts, and the surface of the nut will still be a creamy-ivory color. Break into one of the nuts (careful, they’re hot!). Its center will be a slightly darker color, a sort of beige.

Medium roast: The skins will have cracked on the majority of the nuts and surfaces will still be a creamy-ivory color (just about the same color as the light roast). Centers will be notably darker than the surface color.

Dark roast: The skins will have darkened more and cracked on the majority of the nuts; surfaces will have darkened to a pale tan. Centers will be very dark (and getting darker faster at this point, so get those nuts out of the oven; they’re done!).

Skinning hazelnuts

The time-honored approach to skinning involves roasting and then rubbing them around inside a towel. But this method produces only a 40-60 percent success, depending on the variety of hazelnut. Another method is to simply throw the cooled roasted hazelnuts into a plastic container with a tight lid and simply shake them very violently. The skins will literally peel away from the abrasion. Then tumble the nuts onto a baking sheet, walk outside and blow away the papery skins!