The importance of making free throws

Published 12:36 am Wednesday, February 11, 2015

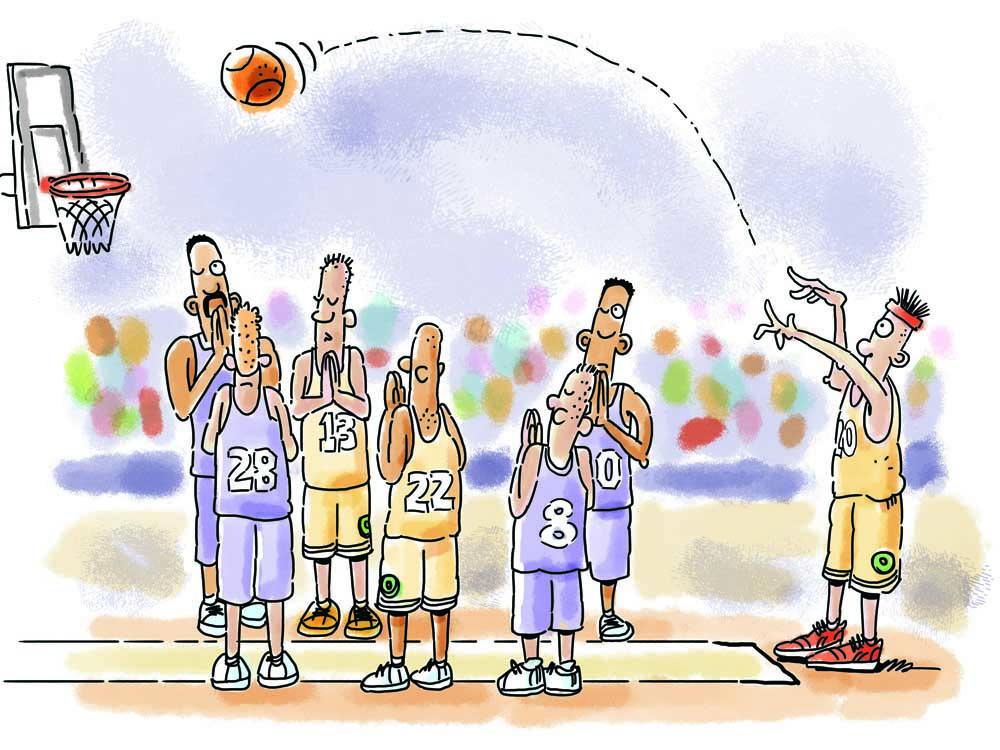

- Greg Cross / The Bulletin

Isaac Newton’s first law of motion is simple: An object, whether in motion or at rest, maintains that status unless acted upon by an external force. Get hot, gain steam and velocity, and that object will continue its course. Cool off, fall into a slump and plateau, and that object remains rested until jump-started.

On the basketball court, Newton’s first law of motion begins 15 feet away from the rim. There, at the free-throw line, lies the external force — the impetus of incalescence or the catalyst of cool-down.

“That one point can change a person’s makeup mentally,” says Nathan Covill, boys basketball coach at Ridgeview. “If they’re having a rough (shooting) night, it can get them in a groove. Or it can change the team’s mental makeup if it’s something that could boil down to the end of a game and you have a team that hasn’t been doing well and they step up to the free-throw line and hit some clutch, pressure free throws to get the (win). That does a lot not only for the individual but for the team.”

The dimensions are constant, players lined up at the charity stripe 15 feet from the rim, which stands 10 feet above the court. The value is fixed, made free throws worth a single point.

But the significance can be much more, says Craig Reid.

“You get a chance to regroup without a defender and have some success,” the 15th-year Mountain View boys coach says. “Mentally, that can flip the button on. ‘OK, I can do this.’ It’s a pretty common remedy for players who are struggling on a particular night: Get to the line and get some rhythm and confidence.”

That axiom is often heard on telecasts, so much so that it has become a cliche. As Covill points out, however, players struggling to make their jump shots sometimes need just one spark, one sight of a shot breaking the lid on the rim and tumbling through the net, to “get into a groove.”

“It’s such a mental game,” adds Sarah Reeves, a Summit sophomore whose squad went a chilly 8 of 21 from the foul line in a loss to Ridgeview recently before following up with a respectable 10-of-17 performance in a victory over Bend. “When you hit the first one or two (free throws), you just have that confidence that, ‘Now I can hit every other shot that I take.’ It’s a huge mental game, and you just need to get in your head that every shot that you take is going in.”

Those freebies fuel players’ confidence levels. They kick into motion, and they stay in motion. Yet there is the second piece of Newton’s law that needs to be addressed. “On the flip side,” Reid says, “‘Hey, this is uncontested and I can’t make it.’”

Says Reeves: “When you miss a few easy buckets or a jump shot that you normally make, it’s really hard to get your mind off of that. I would definitely say that it’s a lot harder if you’re stepping up to the line, knowing you missed the past two or three shots, to step up and knock it down.”

You have more than likely heard about shooters being in “the zone,” dialed in from the floor and seemingly unshakable. That zone, Reid assures, is real. And like an exothermic reaction, gaining heat at the free-throw line and from the field provides energy for teammates.

It is contagious, that feeling of invincibility. Often, it begins at the charity stripe. Foul shots begin to fall. Teammates see the barrier broken. Their mentality shifts: My next shot is going to go down. That mental fortitude is key, says Covill, whose team has made about 75 percent of its free throws this season. After all, as baseball Hall of Famer Yogi Berra put it, 90 percent of the game is half mental.”

“It’s always that mental edge that teams have that are successful,” says Covill, now in his third season with the Ravens. “The successful teams that have a strong mental makeup when it comes time to knocking free throws down or open shots, those are the teams that are usually consistently successful.”

To get to that point, quality repetition is vital, players developing routines they are comfortable with and have confidence in while fine-tuning their shooting technique. As monotonous as the act can seem, free-throw shooting has long held importance in basketball. These days, however, players do not spend enough time on their own developing their shooting forms and routines, Reid notes. That outside work is necessary, Covill adds, as there is not always much time during practice to devote to free-throw shooting.

That is not to say that it is neglected entirely. But rather than simply instructing players to shoot a certain number of foul shots, coaches such as Covill and Reid set up pressure-filled free-throw drills. At Ridgeview and Mountain View, for example, players are required to make free throws lest they face extra conditioning.

“It’s not the same as a game,” says Covill, who recalls his coaches conducting similar foul-shooting drills when he was a player at the University of Montana. “But it’s also pressure because they don’t want to make their teammates run for missing free throws, and they don’t want that consequence.”

The in-game result is a single point for each made foul shot. But that single point, that one snowball, begins to avalanche. Those free throws amass throughout each contest, all while placing opponents in potential foul trouble. For Reid and Mountain View, paced by Davis Holly’s robotic 80-of-83 shooting at the foul line so far this season, those free throws, made and attempted, hold more significance than mere point production.

“The amount of attempts is something we use as a measurement for how aggressive we’re playing, as far as putting pressure on defenses and not settling for jump shots,” Reid says. “That’s important because there’s going to be days when you don’t shoot the ball well as a team and can rely on jump shots too much. We try to really track, on a game-to-game basis, the amount of free throws we’re taking in terms of how aggressive we’re playing.”

The dimensions are constant: the foul line striped 15 feet away, the rim rising 10 feet above the court. The value is fixed: one point for each made free throw.

Yet this is not just a repetitious, seemingly dull act. That foul shot, on point or off line, is a spark. What ensues is physics, as drawn out by Isaac Newton.

—Reporter: 541-383-0307, glucas@bendbulletin.com.