Sunday Reader: A deadly deployment, a Navy SEAL’s despair

Published 12:00 am Sunday, January 24, 2016

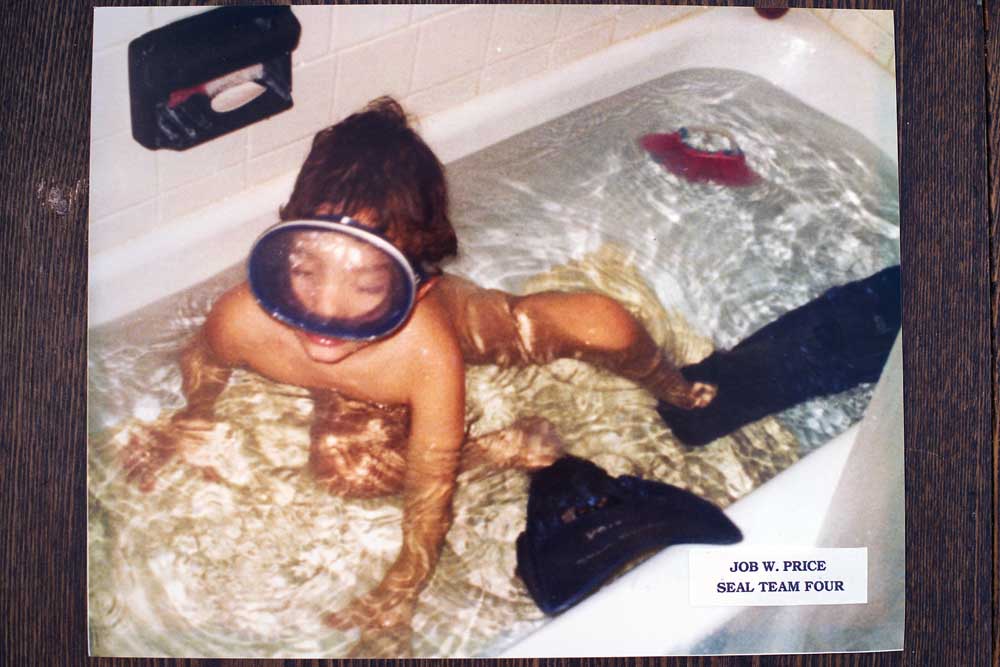

- Handout via The New York TimesAn undated handout photo of Job Price in his youth shows his early aptitude for becoming a Navy SEAL.

It was his last night of what his men were already calling a cursed deployment in Afghanistan.

Cmdr. Job Price had signed off on the final report on the ambush killing of an enlisted Navy SEAL team member. His staff had completed a plan to turn over U.S. military outposts to their Afghan partners, and Price had given an unusually emotional thanks to his team for its service.

His executive officer noticed that the commander’s Sig Sauer pistol was out on his desk that night, Dec. 21, 2012, where he had never seen it before. By the time Price went back to his room, the photograph of his 9-year-old daughter was gone from his desk. In his trouser pocket was a report on the recent death of an Afghan girl in an explosion near a U.S. base.

When Price, the 42-year-old leader of SEAL Team 4, did not appear for a meeting the next morning with an Afghan general, his men searched in the mess hall, in the showers and finally along the row of berths called the Green Mile. In his room, they found him lying in his sleeping bag, the pistol in his hand, a pool of blood beneath the bed.

His death was shocking: Suicide was rare among SEALs, unusual during a deployment in a war zone and unprecedented for a high-achieving SEAL officer. He became the last SEAL to die in Afghanistan.

Everything had seemed to go wrong in Price’s final deployment, which began in September. In short order, he lost four men — two SEAL team members, two Army soldiers — under his command. Relations with the U.S. military’s Afghan partners were tainted by distrust, and the Taliban were growing dominant in the remote region of southeastern Afghanistan where Price’s forces were operating. By then, America’s hopes of defeating the Taliban were fading, and the military’s ambitions were focused on extricating its troops from daily combat.

For a commander of elite Special Operations troops, whose counterparts in SEAL Team 6 had been celebrated for pulling off daring missions like killing Osama bin Laden and rescuing Capt. Richard Phillips from Somali pirates without taking any casualties, the burdens in Afghanistan may have felt especially heavy. In an era of long-distance drone strikes and a reluctance to commit U.S. troops to ground operations, the country’s demand for antiseptic war had already resulted in growing pressure on officers not to lose men in combat.

Price told confidants that his superior had said to him shortly before the team deployed to Afghanistan to bring everyone home. The Navy said the officer, Capt. Robert Smith, typically passed along that common guidance to his team leaders. But with the United States pulling back, other military officers were urging their men to exercise greater caution, several of them said.

“Commanders were no longer judging successful deployments by the tried-and-true standards of enemies killed on the battlefield, but by the number of casualties their own people suffered,” Capt. Milton Sands, a former SEAL team commander, told Navy investigators looking into the death of Price, his friend.

Price left behind no note or explanation, and mental health experts caution that it is often impossible to know definitively what motivated a suicide. Agents from the Naval Criminal Investigative Service interviewed dozens of aides, friends and relatives over the next year and a half before a Navy death review board concluded that Price had killed himself.

One former SEAL team member called the investigators to suggest that the commander might have been murdered, and some colleagues and friends, surprised that no one had heard the gunshot, remain suspicious. His family still struggles to understand how Price, named after the biblical man of faith who overcame adversity, could take his own life.

“I can’t see my son acting that way: no note, no email, no telephone messages, nothing leading up to it,” his father, Harry Price, said in an interview. In his home in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, Harry Price was surrounded by photographs of his son — as a boy in scuba mask and flippers in the bathtub, as a standout high school football player and wrestler, and as a young SEAL team member in camouflage, holding a gun.

But those who saw him close up in Afghanistan provided an intimate portrait of a perfectionist leader unraveling in plain sight. Seemingly overwhelmed by the unpredictable environment that had cost his men’s lives, he became withdrawn and fatigued from lack of sleep and a nagging infection. Aides, who said they had tried to intervene, described themselves as unnerved by his hours of staring into space, his sudden indecisiveness and his aversion to risk.

Price “had a look of defeat,” his adviser on Afghan tribal affairs told investigators. “I personally wondered if he was at a breaking point.”

He had told someone close to him, who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of concern about being ostracized from the tight-knit SEAL community, that team commander was the loneliest position he had ever held. He felt unable to confide in the men above or below him for fear of looking weak.

Several fellow officers saw Price’s death as a cautionary tale of how men were ground down by so many years of fighting. “We like to fancy ourselves as ‘we’re the most resilient guys in the world,’” said Tom Chaby, a retired SEAL captain who headed a U.S. Special Operations Command initiative to encourage troops to seek help for mental health issues. But “after you’re at war, 11 years for Job, we’re all beat up,” he added.

Retired Rear Adm. Edward Winters III, the top-ranking SEAL officer until 2011, said it was hard to predict how officers would react to losing people under them. He said officers who knew Price had reported that he blamed himself for the deaths of his men.

“You realize that guys lost their lives,” Winters said, and that in pulling out of the outposts sooner than planned, “we’re going to leave the place worse than when we got there.”

A ‘hyper-focused’ leader

By 2012, the U.S. troop withdrawal was well underway even though peace talks with the Taliban had faltered. The SEAL team members had to watch for rocket attacks, improvised explosive devices and ambushes. In addition, there had been a surge in attacks by the Afghan security services on their U.S. allies; so-called green-on-blue shootings had become a crisis.

Price understood the dangers going in. He had traveled to Afghanistan that spring for briefings by Cmdr. Mike Hayes, a friend who headed SEAL Team 2 as well as the task force Price would be taking over. He was there when Hayes called in Navy investigators to deal with four Army soldiers’ accusations that three SEAL team members had abused detainees at an outpost in Kalach, in Oruzgan province, leading to one Afghan’s death.

An Air Force Academy graduate — he had been inspired by his uncle, an Air Force colonel during the Vietnam War — and avid sky diver, Price had switched his commission to the Navy for a chance to join the SEALs.

“As he told me, ‘I wanted to be with the best, and they’re the best, so OK,’” his father said.

Even as a young man, he knew his own mind, choosing to attend the public high school in Pottstown instead of the fancy boarding school, the Hill School, where his father was an administrator. He grew into his 6-foot-2 frame, becoming a standout football player and heavyweight wrestler. He played the strategy board game Risk, drove an old Plymouth station wagon with a quirky bulldog hood ornament and loved to quote the Bill Murray military satire, “Stripes.”

His friends and family knew him as a doting husband and father and as a practical joker, a cutup who would be the first to dance at weddings, though not always well. A fellow Navy officer called him “tough and empathetic.” But subordinates in the SEAL teams described him as a workaholic taskmaster, somewhat aloof from his men.

Early in his career, he had been forced to quit a training exercise. Although others thought it did not reflect poorly on him, he was embarrassed by the incident and always felt he had to prove himself, a friend told investigators. (Like others in the NCIS report, the friend’s name was redacted.)

Dennis DeBobes, a retired SEAL commander who served with him, said Price had been stationed in Rota, Spain, when the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks occurred. After that, “Job went into his hyper-focused mode,” DeBobes said in an interview. “There was not a hard job out there that Job didn’t fight for.”

Before he took over SEAL Team 4, Price had deployed a dozen times, including to Afghanistan and Iraq, where a man from his unit was killed, and had been awarded four Bronze Stars. He worked such long hours in the 15 months he spent preparing his team for the 2012 tour in Afghanistan that his executive officer told investigators he had twice informed the commander that he could not keep up.

A succession of losses

Once they hit the ground that September, SEAL units and other troops under Price were spread thin in small outposts across a vast area of southeastern Afghanistan. They worked alongside militias known as the Afghan Local Police, training them and trying to win over the populace. Price found meetings with the villagers difficult, aides recalled, and tried to cut the discussions short, even though hearing the elders out was part of the village-stability strategy.

Still, he was initially upbeat and chatty in emails home, telling one relative to “send some of that donut shop coffee” over. The seven-month deployment was expected to be relatively easy, given that much of it would occur during the winter, which was not the fighting season. But before long, one of the SEALs sustained a gunshot wound serious enough to be sent home.

In late October, an Afghan police officer killed two Army soldiers assigned to the task force, Sgt. Clinton Ruiz and Staff Sgt. Kashif Memon. The assailant came from Chora District in Oruzgan province, where the detainee abuse was said to have occurred months before, though no evidence has emerged to link the episodes.

A week later in Zabul province, east of Kandahar, militants attacked a SEAL patrol. Petty Officer 2nd Class Matthew Kantor, 22, braved machine-gun fire to protect his teammates and was mortally wounded. His death hit Price hard, friends and family said.

He knew that his predecessor running the task force, Hayes, had lost no men. Less than two months into the deployment, his command had already suffered three fatalities. With the exception of a SEAL Team 6 member who died in a hostage rescue operation that fall, Price’s men would be the final SEAL fatalities in Afghanistan. His suicide would bring the toll to 49 in a decade.

On Nov. 24, two days after Thanksgiving, some SEAL Team 4 members and Afghan commandos went on a morning patrol in Oruzgan province. Petty Officer 1st Class Kevin Ebbert, 32, was in the lead position, standing on a ledge.

The cliff face behind him exploded, spraying him with shrapnel. Assailants, presumed to be Taliban militants, had fired an explosive round, most likely a .38-millimeter grenade, and then poured on small-arms fire. Ebbert took a direct hit. He fell from the ledge and landed headfirst in a crevasse, dead.

A military inquiry found that the mission had been appropriately planned. The report noted, however, that images of the target area “did not accurately depict the severity of the terrain.” Price took that as criticism, telling colleagues that he felt the investigating officer had “thrown us under the bus.”

Ebbert was popular and had spoken up for Price when the other enlisted men grumbled. He had joined up after his father, who had served with the SEALs in Vietnam and suffered from post-traumatic stress, died in 2003.

Trained as a medic, he told his family in a video chat on Thanksgiving that he had been accepted to medical school and that his commander was helping him secure an early release from the Navy to prepare. He might be home for good, he said, by mid-January.

Price sent Ebbert’s mother, Charlie Jordan, “a personal handwritten letter, and it was very heartfelt,” Jordan said in an interview. “It was almost a sixth sense I got from it as I read his letter that he was truly moved.”

Some SEAL team members saw Ebbert’s death as a turning point. “It seemed like everyone’s motivation was zapped, and people started complaining that this was the worst deployment/leadership they had seen,” the tribal adviser told investigators, according to the NCIS report.

Signs of strain

Price’s health began to break down. He traveled constantly to visit troops in the field, flying out early in the morning. The deaths of the men under his command were also consuming, with ceremonies, inquiries and paperwork.

In addition, he was receiving “an overwhelming amount of top-down direction,” the tribal adviser told the Navy investigators, with orders to accelerate the closing of most of the outposts.

The command lawyer later told the NCIS that Price had become “increasingly withdrawn, abrupt, erratic, lethargic and disheveled.” One aide observed him sitting with his head in his hands for hours. He was “disengaged,” according to one witness statement, “appearing not to absorb what was being said.”

By that point in the deployment, however, exhaustion was common among the headquarters staff in Tirin Kot, the capital of Oruzgan. Price’s executive officer told investigators that he had served under seven commanding officers in Iraq and Afghanistan, and that “all exhibited similar signs of strain under the pressures of command in combat.”

Chaby, the retired captain, said that as a SEAL commander on deployment, he had kept a sleep log and averaged two hours and 53 minutes a night for seven months. “I suspect Job slept less than I did,” he said.

“I often went to his room late at night and found him lying in bed fully clothed,” Price’s executive officer recalled, according to the NCIS report. “I asked him every night for the last four weeks … what is going on boss? … what is burdening you that I don’t see or know about?” Price responded that nothing was wrong.

In early December, the executive officer and four other top officers and enlisted men staged an intervention. Price acknowledged that Ebbert’s death “weighed heavily on him,” his officers told the NCIS. With no psychologist on site, his men tried to help him get more sleep, pushing back his 9 a.m. “battle update brief” to 11 a.m. and assuring him that they could help work through any problems.

Smith, who was in charge of all SEAL teams based on the East Coast, and Vice Adm. Sean Pybus, who was then the top SEAL admiral and is now deputy commander of the U.S. Special Operations Command, visited from Dec. 7 to 9, touring some of the outposts with Price. Capt. Amy Derrick, a Navy spokeswoman, said that Smith said he “did not notice anything out of the ordinary.” Still, she said, he “reminded Price that sleep, nutrition and exercise are beneficial ways to relieve stress in a combat environment.”

The day they departed, Price was found to have a respiratory infection, which compounded his trouble sleeping and wore him down mentally, the investigative report said. On Dec. 13, medical personnel prescribed 15 tablets of Valium for anxiety and stress. Four days later, he went to the clinic complaining of dehydration and was given two 500-milliliter bags of saline. He asked the medics not to document the visit in his medical record.

Even though the military has stepped up efforts to identify and treat mental health problems, many SEAL team members say they fear that acknowledging such problems is a career ender. There are no definitive statistics on suicides by current and former SEALs, though at least three have been publicly confirmed.

Little more than a month before Price died, his wife, Stephanie, forwarded him an email about the suicide of Robert Guzzo, 33, a former SEAL team member who had struggled with post-traumatic stress. “Sad,” she wrote, according to the NCIS report. “Luv u.”

The final days

On Dec. 16, an explosion shook a valley in Oruzgan. U.S. personnel nearby heard it, and a team of Afghan special forces found the body of a little girl.

The site, close to an outpost Price was responsible for overseeing, had been used for mortar firing, but a U.S. military report said that no unexploded ordnance had been left on the ground and that the only dud had been cleared, leaving the cause of the blast a mystery.

Stephanie Price would later tell investigators that her husband was “upset because of local national children being brought to their base to receive treatment for injuries caused by IEDs and random gunfire.”

She had been concerned about him for a while and tried to cheer him in mid-December by sending their daughter’s school progress report, noting how well she was doing in music, according to the NCIS document. One of Price’s friends told investigators that when he stopped by the couple’s house in Virginia to deliver a Christmas present for the girl, Stephanie Price said she was worried that her husband “seemed a little down.” She also told the wife of one of her husband’s aides that he seemed to be under a lot of stress.

On Dec. 21, Price seemed more at peace, smiling and making jokes, and announced that he had finally started to sleep again and was feeling better, his staff said. A Christmas card from his parents had arrived, and he was working with his wife on a Christmas note to the spouses of SEAL Team 4. He hugged his executive officer and thanked the others with obvious emotion.

He and his staff also put two difficult issues behind them, as he signed off on the report on Ebbert’s death and his aides completed a final briefing on plans to turn over the outposts to the Afghans.

The next morning, a colleague could not find Price for a meeting with an Afghan general, so he knocked on the door to his room twice, found it unlocked and went in. It was not until he fully entered the room that he noticed all the blood. He could not detect a pulse in Price’s left wrist, and found his skin cold.

His daughter’s photo was on his desk, and the folded report on the death of the Afghan girl was still in the pocket of his utility trousers, slung across a nearby couch.

For members of his family, questions linger three years after his death. Their doubts were exacerbated, they say, by how few of his comrades visited them afterward and by the difficulty they had wresting documents about his death from the military. They still wonder how no aides heard the gunshot — some recalled only an indistinct noise — in the cramped quarters and whether all the forensic evidence was analyzed properly before his body was cremated.

“It’s hard with the secrecy and the way no one is willing to talk to us,” said his sister, Bronwyn De Maso. “No matter how he died, if he did kill himself, he was a casualty of war.”