In Toledo, layers of Spanish history

Published 4:00 am Sunday, December 23, 2012

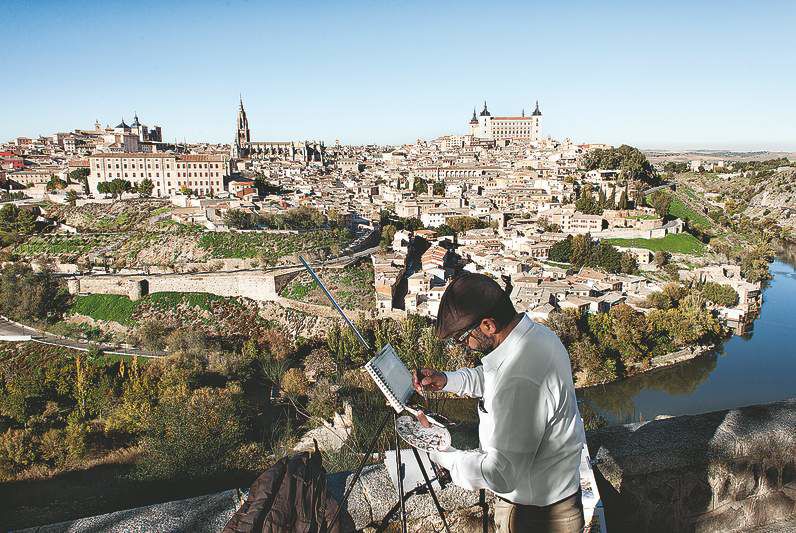

- A painter works on a piece in Toledo, Spain. The whole of Toledo is a historic district that feels like a living museum.

The rain and morning fog had left the cobblestones of the old bridge too slippery to jog on. I had to get to the other side of the Tagus River to get a real view. I turned and looked.

The city itself sat on the hill like a medieval Oz, the river wrapped around it like a moat. There were two layers of castle walls, festooned with gargoyles, eagles and crests. On top of the bluff was the Alcazar, which looked out over the city’s patchwork of Manchegan red clay tile roofs and the spires and belltowers of churches. The bells started to peal, eventually crescendoing to an explosion of noise that sounded like the finale of a fireworks show. It was still very early in the morning. Holy Toledo, I thought.

Trending

“That’s what the old ladies say — ‘Holy Toledo!’ — when they are walking up and down these streets,” my guide, Manuela Carrasco, told me later that afternoon as we made our way through the windy maze of Spain’s old capital.

Some cities have old quarters. But the whole of Toledo is a historic district, indeed a Unesco World Heritage site, remaining largely intact throughout the many violent takeovers of Spain. “We have the church to thank for that,” Manuela said.

Because Toledo was considered the holiest city in Spain in the Catholic faith, its invaders were careful not to destroy hallowed ground. So it survived the Moors, Visigoths, the Spanish Civil War. The Alcazar, or castle, is an exception — it has been destroyed and rebuilt countless times since the Romans marched through.”The rest of Toledo, it’s never been touched,” Manuela said.

In a city that feels like a living museum, buildings and other remnants easily transport visitors to a different era, no small feat just a 30-minute train ride away from the cosmopolitan riches of Madrid. I didn’t even have to look up any schedules to get there since the train departs every hour on the half-hour.

Munching in La Mancha

I arrived around dinnertime, and checked into Hostal del Cardenal, a hotel that was an easy pick out of my guidebook because of its location: it’s literally built into the old city wall. The space — once the quarters for a cardinal in the 18th century — fills a spot where soldiers must have kept a lookout. For less than $100 a night, it was a bargain. There were elaborate patios, fountains and gardens. The restaurant was run by the same owners of Botin, the oldest restaurant in Madrid, famous for its cuchinillo, roasted suckling pig, for more than 300 years. As tempting as the meat looked coming out of the wood oven in cast-iron pans there, I was anxious to get moving and left the hotel for dinner.

Trending

La Mancha, the province in which Toledo sits, is a high, arid place. The result is a cuisine based on the most elemental ingredients, like sopa de ajo, a broth made with water and garlic, and migas, a concoction of moistened bread crumbs cooked in olive oil and garlic and chunks of ham if available.

I ventured off to find Toledo’s most prized dish: perdiz estofada, a local red-tailed partridge that’s a favorite of hunters. Outside the city wall, down the Paseo Circo Romano, I discovered Venta de Aires, which first started serving the dish in 1891. It’s also where Surrealists like Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali formed the Order of Toledo, got wildly drunk and paraded through the ancient city in costumes. Now it’s been rebuilt with glassy, modern flourishes.

The perdiz was an element of nearly every dish at Venta de Aires, even forming the base of a delicate yet sumptuous creamed crab and eggplant soup. The perdiz itself came served on the bone, with a small mountain of caramelized onions that were sauteed in sherry vinegar from Andalusia, in southern Spain. Dessert was another Toledo specialty: marzipan, with a semi-cooked egg in the middle and with ice cream on top.

Walking through the ages

I usually explore a city by picking a direction and walking that way. But there were too many layers of history to untangle alone in Toledo. So the next morning I decided to hire a guide at the tourist center to help me make sense of the place.

Manuela met me at the hotel, and we entered the city through the massive Visigoth gate, then set out on a dark cobblestone street that was more like a tunnel because a convent had been built above it. The entire city is like that — because it is so old, one layer is built on top of another. All the layers have made Toledo a destination for treasure hunters. The city has been rumored to house gold stockpiled by the church, and the lost table of King Solomon. But after digging under churches and buildings, none of the fabled relics have been uncovered.

“What we find mostly is a lot of bones,” Manuela said. “A lot of femurs and skeletons. We like to say, ‘In Toledo, there are more dead people than alive.’”

On street level, we passed nuns in habits and tourists like me passing through. Most Toledans now live outside the city, Manuela said, though some families have remained in their wood-framed Manchegan homes for centuries.

We stopped in what appeared to me to be an old church. Inside, the ceilings were high; the pillars, wedding cake white and topped with ornate horseshoe arches. Once I looked around, the space felt more like a mosque. But upon inspection, many inscriptions were written in Hebrew. Such were the baffling charms of Sinagoga de Santa Maria la Blanca, a Jewish house of worship founded in 1203, remodeled and used as a mosque by the Moors, used later as a church, and now serving as a tourist sanctuary run by nuns in the Jewish quarter of town.

Nowhere are the layers of Toledo more evident than in the rubble of the Alcazar, the only site in Toledo that has been attacked and bombed through the ages. City officials have preserved the ruins under one roof. Inside, against the rocky incline that Toledo is built upon, one can see the layers of debris: the palace the Romans constructed in the third century; traces of the Moors and Visigoths; and finally the warring factions that battled for Spain during the Civil War.

We left the castle, walked down another road, up a hill, down another. Toledo may look as if it is was designed by M.C. Escher, but its most famous resident artist was El Greco, the Renaissance painter from Crete who moved here in 1577, desperate for commissions from the church. In Toledo, he toiled and created some of his later masterpieces like “View and Plan of Toledo.”

The works are on display inside Museo del Greco, a museum in his honor that recently reopened after five years of renovations. There was a line out front. I debated going in. It was late in the day, and there was the cochinello back at the hotel restaurant I had to try before taking the train back to Madrid. Besides, I’d had my own glance of El Greco’s works. They were on display in the window of the gift shop in his honor, too, rolled up into posters and for sale.

“The church didn’t pay him for two years, he had no money,” Manuela said, explaining that Toledo’s biggest draw had basically lived as a pauper. “If El Greco were to wake up from his tomb and see this museum, see this gift shop, I have no idea what he might say.”

“Holy Toledo?” I suggested.

“Holy Toledo,” Manuela said.