Talks by Eugene author Debra Gwartney

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 12, 2010

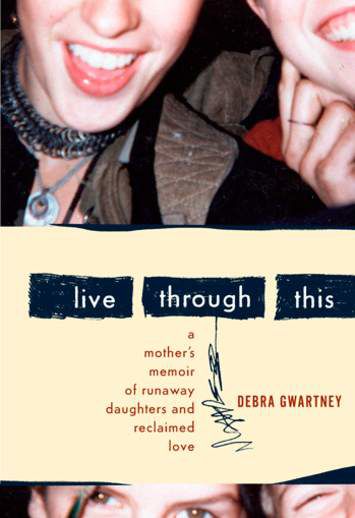

- “Live Through This” chronicles author Debra Gwartney’s struggles with runaway teenage daughters.

Debra Gwartney gives the kind of interview that makes a parent of young kids go “Wow.”

And not “Wow” in a good way. That’s “wow” in a lost-for-words way.

Today, author Debra Gwartney, 53, is the proud mother of four mature, responsible daughters. Her youngest two are in college. Her second-oldest just graduated with honors from Smith College, and her oldest is a married mother running a large Southern Oregon farm with her husband.

That kind of stability was not in the mix more than a decade ago, when the two oldest daughters, Amanda, now 30, and Stephanie, 28, entered their teens and began running farther and farther from home. At one point, Stephanie got as far away as Austin, Texas, and was gone for a year.

Wow.

In her memoir, “Live Through This,” released in paperback earlier this year, Gwartney recounts the drama, misery and glimmers of hope of those years.

Gwartney, who lives in rural Lane County near the headwaters of the McKenzie River, will read from the book during appearances Friday and Saturday at Paulina Springs Books (see “If you go”).

The trouble, Gwartney says, began in the early 1990s, after her first marriage ended in divorce. She packed up her four daughters and left their home of Tucson, Ariz., for a job as editor of Eugene Weekly.

Gwartney describes Eugene at that time as “insular,” and says assimilating was difficult for a single mother juggling full-time work and her four daughters, who missed their father as they endured the battlefronts of a new school and new town.

In their early childhood, all her daughters had been “great, normal, happy kids who were doing great in school, had lots of friends,” recalls Gwartney. The girls’ father soon remarried and fathered another child, and though not out of their lives altogether, “I had custody of the girls,” says Gwartney. “I was pretty much their sole parent for most of the time. He was far away. It wasn’t like he could come up for dance recitals.

“Everything happened too fast, at once, I think was the problem. My daughter Amanda … when we moved to Eugene, she was 13, so she was going through a lot of changes in her own body and mind, and separating from her father, her place, her friends. That was what kind of dug a hole that she never could get out of, or didn’t get out of for years.”

Wow.

Recipe for rebellion

Eugene was nice, Gwartney says, but “people have lived there for many years or even generations, and they don’t really embrace newcomers, or they didn’t at that time. I had trouble making girlfriends, and women friends. And Amanda in middle school — middle school was ruthless.”

Amanda attended Roosevelt Middle School in Eugene. “The kids who were well-ensconced there were, ‘Well, who are you?’” Gwartney recalls. “‘Get away from us. We’re the French immersion students, and you’re nothing.’ All of that hierarchy that suddenly rears its head in middle school was just really hard on her.”

Amanda began rebelling, and after she and another girl lit paper on fire in a school bathroom sink, she was arrested for arson, a felony.

“So she already felt very ostracized, and all of a sudden they’re telling her you can’t go on any field trips, you have to sit and eat lunch in a room by yourself. So she came out of that year extraordinarily angry. The spiral began right there.”

By the time Amanda was 15 and Stephanie was 13, the pair began running away.

“In the meantime, I am working full time. I have four kids, and I just didn’t focus in on this like I should have. I didn’t see how very sad and troubled she was,” Gwartney says.

When Stephanie was away for a year, “It was really horrible,” says Gwartney, still sounding shell-shocked. “I never, ever want to go through anything like that again. It was truly soul-numbing. I just had to somehow endure,” she said. “I was sending out posters all over the country.”

Stephanie turned 15 on the road. “At the end of that year, she called me one day and said, ‘I’m in Austin, Texas.’ She got herself that far away. She’d adopted a dog that was very sick. She wondered if I’d send money for the dog, and I said, ‘No, but I’ll send money to get you and the dog home.’

“She hung up on me, that time, but it did open the communication. It was some weeks before I did get her back, (and) it sure was not easy after that. But gradually it did get better. Took a long time.”

“They’re doing so well now,” Gwartney says. Today, Stephanie is “thriving.”

No support

As a mother, Gwartney says she’s asked herself why she didn’t see any of it coming. Yet, asked if there were warning signs, she replies, “No, I don’t think there were.”

She does know that trying to work full time while raising four daughters herself, with no outside help, was a huge and daunting task. “I kept telling myself, ‘A good mother would manage this.’ I couldn’t admit to myself that it was way beyond what I was capable of doing,” she says.

“I have often thought back, ‘If I’d only had a support network.’ When I moved to Eugene with four little girls, I didn’t know a single person. And that was a mistake. … We needed other people. My two youngest daughters, they were just great, happy, well-adjusted kids all the way through, and I think that’s because we’d been in Eugene for 10 years, and I finally had some friends, and they had friends,” Gwartney says. “Without a network, parents really suffer, and so do their kids.”

Her adult daughters have a love-hate relationship with the book, Gwartney says. Her youngest was working at the University of Oregon bookstore when “Live Through This” debuted.

“When it first came out, someone came up to the counter with it, and said, ‘I used to know these girls!’ She just kept her mouth shut and didn’t say, ‘Well, I’m one of them,’” Gwartney says

In her own career, Gwartney went on to report for The Oregonian. Today, she’s married to the writer Barry Lopez, with whom she co-edited the 2006 book “Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape,” and teaches nonfiction writing at Portland State University.

Now that her oldest daughter, Amanda, is a mother herself, do they ever discuss the subject of impending teen years?

“We’ve talked about it some. Of course, she gets very defensive, as young parents do. ‘Oh, my child is never going to do that. That’s never going to happen to me.’ … She has said to me, ‘I would go crazy if I didn’t know where my children were for 20 minutes.’”

Wow.

She’ll know whom to come to for advice. She’ll likely hear the same thing Gwartney told The Bulletin: “Find a network. Get that support system. Don’t be afraid to tell somebody that your child is threatening to run away. … I was so ashamed that this was happening that I wasn’t really saying anything. Don’t live in denial. Get out there and tell people, ‘I need help.’”

If you go

Who: Author Debra Gwartney

When:

• 6:30 p.m. Friday at Paulina Springs Books, 422 S.W. Sixth St., Redmond (541-526-1491)

• 6:30 p.m. Saturday at Paulina Springs Books, 252 W. Hood Ave., Sisters (541-549-0866)

Cost: Free