Who owns the West?

Published 7:00 am Friday, September 24, 2021

- Foreign interests2

In recent decades, foreign investors have bought more than 35 million acres of U.S. farmland worth $62 billion — about 2.7% of all privately held land nationwide, an area larger than New York state.

And foreign investors continue to buy, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Some American farmers view foreign investment as beneficial, expanding markets and access to capital. Others view it as a threat to national security, food system resiliency and land access.

The issue surfaced as a hot topic in Congress this summer after Rep. Dan Newhouse, R-Wash., proposed legislation to ban the Chinese government from buying U.S. farmland.

“Allowing this practice to continue would lead to the creation of a Chinese-owned agricultural monopoly and pose an immediate threat to U.S. national security and food security,” Newhouse said.

Newhouse is right that China is a big player. According to 2018 USDA data, Chinese investment in the agricultural sector has grown tenfold in a decade. But most of China’s investments have been in the meat sector and the Midwest.

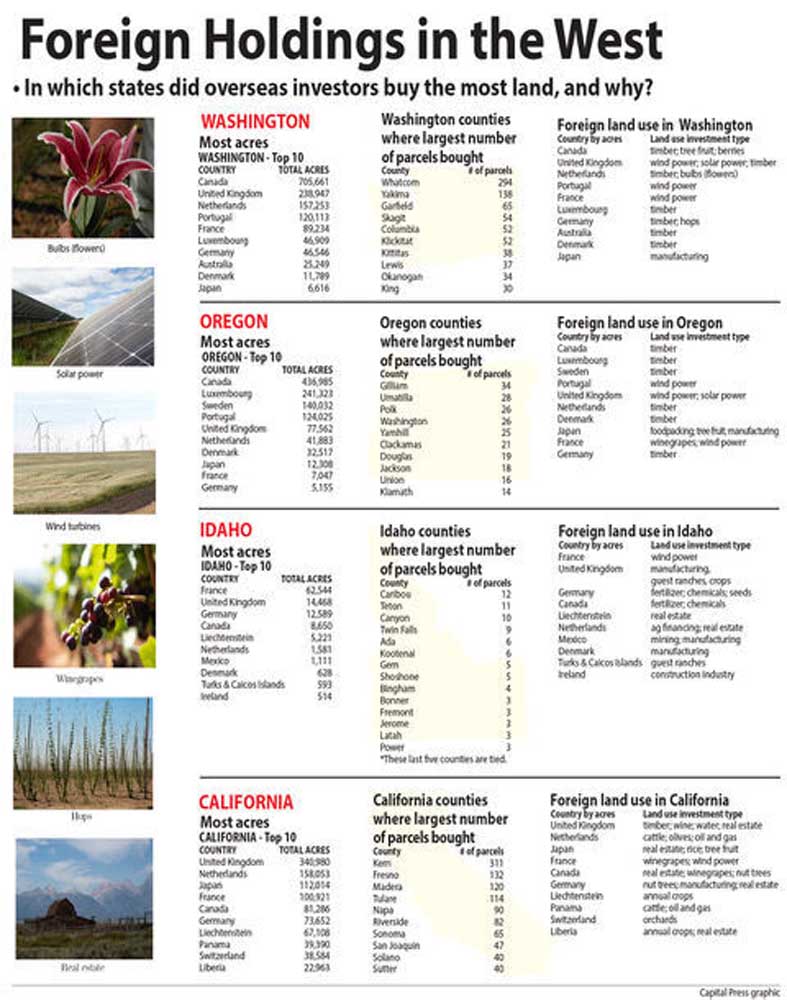

Investment often takes a different shape in the West. In four Western farm states — Oregon, California, Washington and Idaho — China doesn’t even make it onto the list of top 10 investors.

So, who is buying farmland in the West, and what are their intentions?

Big players in the West are from Canada, Europe and Japan. Top investments include timber, tree fruit, wine grapes, manufacturing and processing, real estate development and renewable energy.

Tracking buyers

To uncover which countries are investing in American soil and why, the Capital Press requested a database of public records from USDA through the Freedom of Information Act.

The database is called the Agricultural Foreign Investment Disclosure Act, created in response to a law Congress passed in 1978 requiring foreign buyers to report transactions.

The database covers the years 1900 through 2019, although records are patchy prior to 1978. USDA is still compiling the 2020 list, said Amanda Heitkamp, USDA spokeswoman.

The database tracks investments in cropland, pastureland, forestland and “other” farmland.

According to USDA staff, outside investments are on the rise. Filings show foreign holdings of American farmland increased by 141% between 2004 and 2019.

This, experts say, is a conservative estimate. That’s because, although the 1978 law required foreigners to report land purchases, the requirement is not enforced.

Joe Maxwell, president and CEO of Family Farm Action, a group that advocates on behalf of small family farmers against corporate behemoths, said he believes the database, though useful, “woefully underreports” the number of foreign investments.

“It’s just the tip of the iceberg,” he said. “We believe what’s being reported is just a thimbleful of what’s actually out there.”

The only way to accurately trace all foreign holdings, land use experts say, would be to piece together records from every county assessor’s office in the nation — a mammoth project.

“It’s just really difficult to track,” said Jim Johnson, land use and water planning coordinator at the Oregon Department of Agriculture.

Changing hands

Farmland, once in someone’s hands, doesn’t always stay there.

Although USDA reports foreigners hold an interest in about 35 million acres, that’s assuming every foreigner who ever bought farmland held onto it. And that’s just not the case.

The database, cross-referenced with public business filings and sales records, reveals that many foreign investors have sold farmland they once held. Dozens of foreign owners have dissolved businesses, sold land to domestic or international buyers, gone bankrupt or experienced foreclosure.Foreign investment comes in many flavors: from individuals, corporations, institutions, associations, estates, trusts and partnerships.

Tracking names recorded in USDA’s database, the Capital Press called and emailed dozens of foreign buyers across the West, revealing a tapestry of people and stories.

Some buyers have big names, like the Haub Brothers Enterprise Trust, which is associated with Erivan Haub, a German grocery store magnate whose trust bought thousands of acres of Washington farmland.

Other buyers have straddled continents, like a young British farmer running a biogas business and operating farm properties in both Oregon and the United Kingdom.

Still others have been immigrants headed West to build a dream, like a Dutch flower grower who, with his wife and baby in tow, took out loans to build a bulb business.

Foreign-owned farmland in Oregon

Foreign buyers have purchased 1.2 million acres of Oregon farmland — roughly 7.5% of the state’s farm acreage, according to the 2017 U.S. Census of Agriculture.

Top investors are from Canada, Luxembourg, Sweden, Portugal and the U.K. Investors from the first three countries have invested mainly in timber; investors from the latter two in wind and solar power.

Reflecting microclimates and the character of the land, investments vary from county to county. Gilliam and Umatilla counties, where foreigners have bought the largest number of parcels, have mainly seen renewable energy developments. Polk County has seen timber and wine investments.

Whether foreign investment is good or bad is a matter of disagreement among Oregon farmers.

Solar power on farmland is especially controversial, and groups including the Oregon Farm Bureau and 1000 Friends of Oregon have raised alarms.

“We’re constantly fighting the misconception that agricultural land is vacant land. It’s not,” Kathryn Jernstedt, president of Friends of Yamhill County, told the Capital Press this summer.

Farmers view other investments more favorably.

Before the 1970s, Oregon’s wine industry was virtually nonexistent. But as pioneers started making high-quality wine, it grabbed the attention of international investors.

The first French family to buy an Oregon vineyard was the Drouhin family, which has been making wine since 1880 in the Burgundy region of France.

After visiting Oregon, Robert Drouhin and his daughter, Veronique, decided to buy land in 1987.

“The Oregon wine community was so welcoming to the family,” said David Millman, the company’s CEO and president. “This wonderful, respected family investing in Oregon of all places was this huge, huge boost — a sort of validation.”

Today, more than a dozen European companies own Oregon vineyards.

Critics, including Maxwell of Family Farm Action, said there should be a distinction between control and investment. Investment is good, he said — a foreign entity investing dollars and receiving a percentage of profits. But Maxwell said foreigners should not hold land or management positions.

Most leaders in Oregon’s wine industry disagree.

“While foreign investment has caused some concern within the Oregon wine community, overall, it has been viewed as a positive,” said Sarah Murdoch, spokeswoman for the Oregon Wine Board. “Our wines are now recognized as being world-class.”

“These newcomers,” she said, treat Oregon growers with respect and have brought “new energy, new ideas and greater national and international marketing capacity.”

Oregon’s Legislature has made no laws restricting foreign ownership of private farmland.

The future

Foreign investment in the West takes a different shape than in the Midwest.

China’s investment strategy in the Midwest and the East is clear, said Maxwell of Family Farm Action. A Chinese company, WH Group, first purchased meat processing infrastructure such as Smithfield Foods, the world’s largest pork producer. Then it bought cropland — Midwestern wheat, corn and soybean acres — to feed those hogs.

In the West, different themes emerge, including an interest in renewable energy, high-value perennial crops, real estate — and more recently, land purchased for its water rights.

So, what’s next? Though farmers in the West differ in their opinions on whether foreign investment is bad, good or a mix, most with whom the Capital Press spoke said something should be done.

Watch Congress, Maxwell said, where debates about China have opened the much broader conversation about foreign investment as a whole.

Change, he said, may be on the way.