Textile factories are humming, but not with workers

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 22, 2013

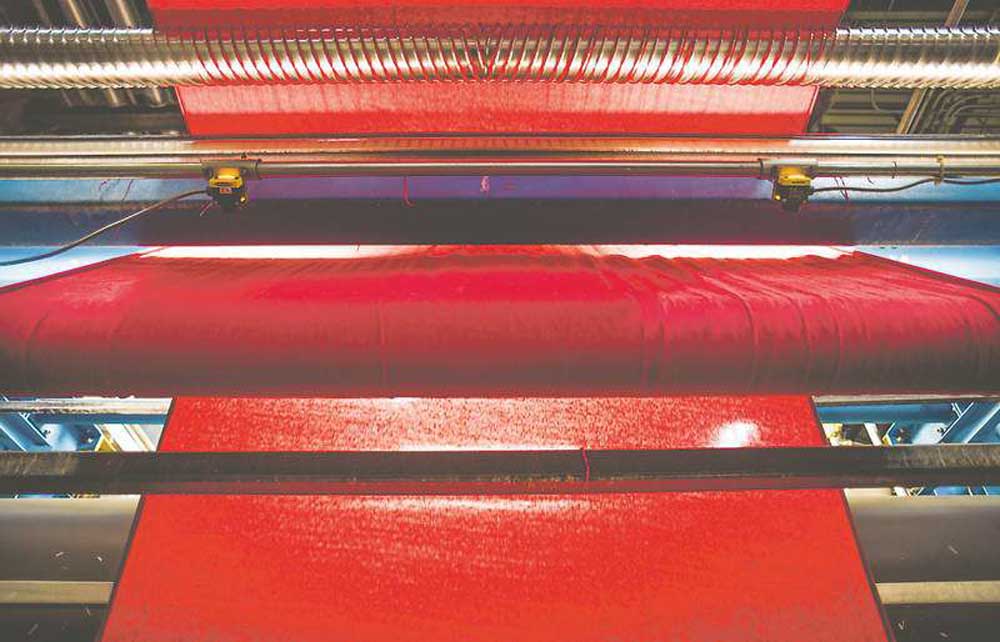

- Fabric is processed at the Carolina Cotton Works plant.

GAFFNEY, S.C. — The old textile mills here are mostly gone now. Gaffney Manufacturing, National Textiles, Cherokee — clangorous, dusty, productive engines of the Carolinas fabric trade — fell one by one to the forces of globalization.

Just as the Carolinas benefited when manufacturing migrated first from the Cottonopolises of England to the mill towns of New England and then to here, they suffered in the 1990s when the textile industry mostly left the United States.

It headed to China, India, Mexico — wherever people would spool, spin and sew for a few dollars or less a day. Which is why what is happening at the old Wellstone spinning plant is so remarkable.

Drive out to the interstate and you’ll find the mill up and running again. Parkdale Mills, the country’s largest buyer of raw cotton, reopened it in 2010.

Bayard Winthrop, the founder of the sweatshirt and clothing company American Giant, was at the mill one morning earlier this year to meet with his Parkdale sales representative. Just last year, Winthrop was buying fabric from a factory in India. Now, he says, it is cheaper to shop in the United States. Winthrop uses Parkdale yarn from one of its 25 U.S. factories and has that yarn spun into fabric about 4 miles from Parkdale’s Gaffney plant, at Carolina Cotton Works.

Winthrop says U.S. manufacturing has several advantages over outsourcing. Transportation costs are a fraction of what they are overseas. Turnaround time is lower. Most striking, labor costs — the reason all these companies fled in the first place — aren’t much higher than overseas because the factories that survived the outsourcing wave have largely turned to automation and are employing far fewer workers.

And while Winthrop did not run into such problems, monitoring worker safety in places like Bangladesh, where hundreds of textile workers have died in recent years in fires and other disasters, has become a huge challenge.

“When I framed the business, I wasn’t saying, ‘From the cotton in the ground to the finished product, this is going to be all American-made,’” he said. “It wasn’t some patriotic quest.”

Instead, he said, the road to Gaffney was all about protecting his bottom line.

That simple, if counterintuitive, example is changing both Gaffney and the U.S. textile and apparel industries.

In 2012, textile and apparel exports were $22.7 billion, up 37 percent from just three years earlier. While the size of operations remain behind those of overseas powers like China, the fact that these industries are thriving again after almost being left for dead is indicative of a broader reassessment by U.S. companies about manufacturing in the United States.

But as manufacturers find that U.S.-made products are not only appealing but affordable, they are also finding the business landscape has changed. Two decades of overseas production has decimated factories here. Between 2000 and 2011, on average, 17 manufacturers closed up shop every day across the country, according to research from the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

Now, companies that want to make things here often have trouble finding qualified workers for specialized jobs and U.S.-made components for their products. And politicians’ promises that U.S. manufacturing means an abundance of new jobs is complicated — yes, it means jobs, but on nowhere near the scale there was before, because machines have replaced humans at almost every point in the production process.

Take Parkdale: The mill here produces 2.5 million pounds of yarn a week with about 140 workers. In 1980, that production level would have required more than 2,000 people.

Curse of long distance

When Bayard Winthrop founded American Giant, he knew precisely what he wanted to make: thick sweatshirts like the one from the Navy that his father used to wear.

They required a dry “hand feel,” so the fabric would not seem greasy to the touch, and a soft, heavily plucked underside. Winthrop had already produced sportswear overseas, so he looked there for the advanced techniques and affordable pricing he needed.

He wanted to sell his hooded sweatshirt for around $80, between the $10 Walmart version, made in China, and the $125 Polo Ralph Lauren version, made in Peru. He was insistent on cutting and sewing the sweatshirts in the United States — a company called American Giant couldn’t do that part overseas, he felt — but wasn’t picky about where the fabric came from.

With the help of a consultant, he settled on a mill in Haryana, India, that could make the desired fabric. After several months of back-and-forth, Winthrop was ready to ship his first sweatshirts in February 2012.

But he was frustrated with the quality and the lengthy process. By October of last year, Winthrop had moved production to South Carolina. Now it takes just a month or so, start to finish, to get a sweatshirt to a customer.

“We just avoid so many big and small stumbles that invariably happen when you try to do things from far away,” he said. “We would never be where we are today if we were overseas. Nowhere close.”

Winthrop and his team visit Carolina Cotton Works and Parkdale whenever they want, check on quality and toss ideas around with the managers. And, he says, the cost is less than in India.

Where Winthrop relies on labor — the cutting and sewing of the sweatshirts, which he does in five factories in California and North Carolina — is where the costs jump up. That costs his company around $17 for a given sweatshirt; overseas, he says, it would cost $5.50.

But truth be told, labor is not a big ingredient in the manufacturing uptick in the United States, textiles or otherwise. Indeed, the absence of high-paid U.S. workers in the new factories has made the revival possible.

“Most of our costs are power-related,” said Dan Nation, a senior Parkdale executive.

March of the machines

Step inside Parkdale Mills and prepare to be overwhelmed by machines.

The ceilings are high and the machines stretch city block after city block — this one tossing around bits of cotton to clean them, that one taking 4-millimeter layers from different bales to blend them.

Only infrequently does a person interrupt the automation, mainly because certain tasks are still cheaper if performed by hand — like moving half-finished yarn between machines on forklifts. Beyond that, there is little that resembles the mills of just a few decades ago.

Tell people about a textile plant and “their image is ‘Norma Rae,’ and everyone’s sick and dirty and coughing and it’s terrible,” said Mike Hubbard, vice president of the National Council of Textile Organizations.

Not here. The air-cleaning room, where air is washed 6.5 times an hour to get contaminants out, could be a modern-art installation, with liquid raining into pools of water. Along the ceiling, moving racks like those at a dry cleaner snake throughout the factory, carrying the finished yarn to a machine for packaging and shipping. That machine has enough lights and outlets on it that it resembles a music studio soundboard.

For Parkdale, the new technology has been its salvation.

Founded in 1916, Parkdale is the largest buyer of raw cotton in the United States. In the 1960s, when its current chairman, Duke Kimbrell, took over, it was a single plant with a couple of hundred workers.

Seeing that other plants in the area were streamlining their businesses and ceasing to make their own yarn, Parkdale supplied yarn to nearby manufacturers like Hanesbrands. Business flourished, and Parkdale acquired competitors and soared until the 1990s.

That’s when its clients started fleeing the United States.

The North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994 was the first blow, erasing import duties on much of the apparel produced in Mexico. The Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, when currencies collapsed, added a 30 to 40 percent discount to already cheaper overseas products, textile executives said. China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001 and quickly became an apparel powerhouse, and, as of 2005, the WTO eliminated textile quotas.

In 1991, U.S.-made apparel accounted for 56.2 percent of all the clothing bought domestically, according to the American Apparel and Footwear Association. By 2012, it accounted for 2.5 percent. Overall, the U.S. manufacturing sector lost 32 percent of its jobs, 5.8 million of them, between 1990 and 2012, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. The textile and apparel subsectors were hit even harder, losing 76.5 percent of their jobs, or 1.2 million.

“With all the challenges that we’ve had with cheap imports, we knew in order to survive we’d have to take technology as far as we could,” said Anderson Warlick, Parkdale’s chief executive.

“We’ve been able to be effective here because we invested in our manufacturing to the point that labor is not as big of an issue as far as total cost as it once was. It’s allowed us to be able to compete more effectively with foreign countries that pay, you know, a fraction of what we pay in wages. We compete with them on technology and productivity.”

Back from the dead

All that automation has made working in the mill — which once meant mostly dead-end jobs for people with no other options — desirable for many people.

Howard Taggert, 86, got his first mill job in 1948 after high school.

“By being a color, yeah, you’ve got the worst jobs there was in textile,” said Taggert, who is African-American. “It was rough, but it was a living. We made a living.”

He started by opening cotton bales, which involved striking an ax onto a metal tie around the bales — a dangerous job, given that a spark from metal striking metal could ignite a room full of cotton. The dust was so thick that he couldn’t see to the next aisle, he said. He was paid 87 cents an hour.

“I had to. I didn’t have no other choice,” he said of working in the mills.

The work was so bad that Taggert refused to let his children go into mill work. He might be surprised to hear about Donna McKoy, who went back to work in a mill even after earning an associate degree in criminal justice.

She earns $47,000 a year and says the perks, like health care, an in-house nurse and monthly management classes for supervisors, are good. She recently bought a three-bedroom house and owns a car.

“I have a comfortable life,” she said.

Still, some Parkdale employees worry about the future. They’ve seen too much hardship in the textile industry to be overly hopeful. Scott Symmonds, 40, of Galax, Va., works as a technician for two plants in the area. He never planned on manufacturing work, but after time in the National Guard in Iraq, his home went into foreclosure and he had trouble getting work because of his low credit score and lack of a college degree. As a teenager in rural Iowa, he knew people who worked in manufacturing and watched two plants go out of business.

“I saw how they would come home dirty, smelly and often injured,” he said. “I didn’t want that.”

But he needed a job. Symmonds started as a spinner, then got a job on the packing line and then snagged a technician’s job after a technical-aptitude test. He earns $15 an hour, which he says is better than what competitors pay. He fears, though, that his higher pay could become a liability.

“We are making far more money than our counterparts in China or other nations,” he said. “We can’t afford to take a big enough cut in pay to be on an even level with those places.”