A pilgrim’s progress, or maybe lack thereof

Published 12:00 am Sunday, August 17, 2014

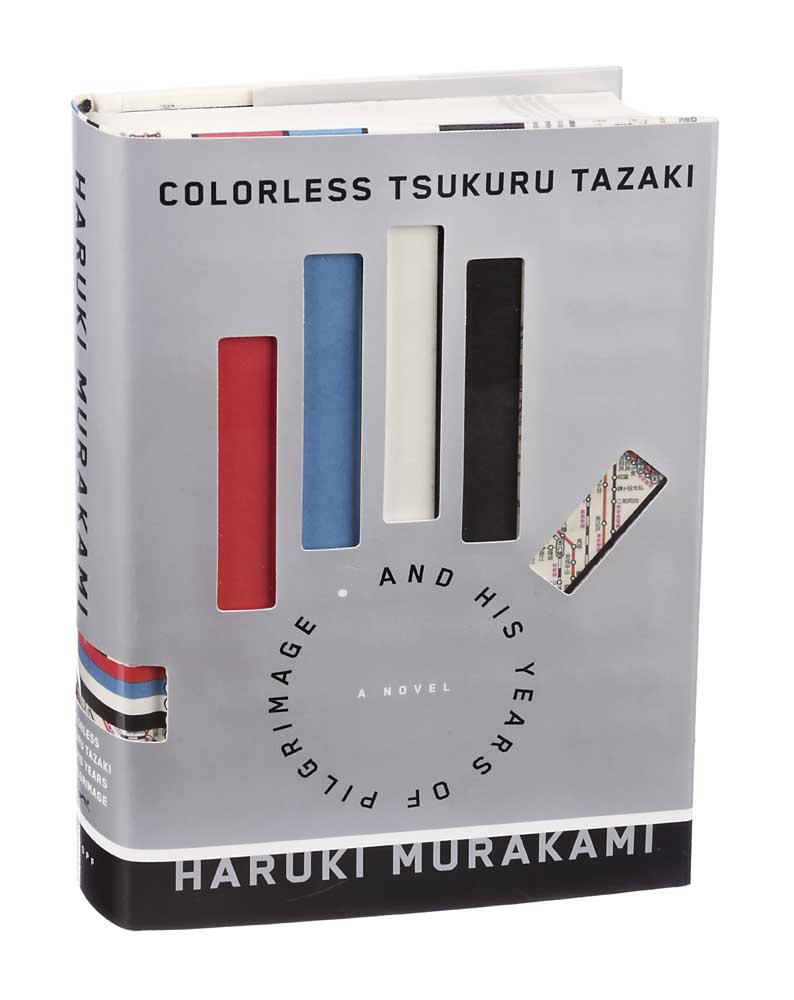

- Sonny Figueroa / The New York TimesThe novel "Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and his Years of Pilgrimage," by Haruki Murakami. Published by Alfred A. Knopf.

“Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage”by Haruki Murakami, translated by Philip Gabriel (Alfred A. Knopf, 386 pgs., $25.95)

Chalk up some of Haruki Murakami’s rock-star status to the way he evokes the self-pitying narcissism of youth. At 65, Murakami can still channel the agonies of a high school student who thought that he and his four best friends were the center of the universe — until the cruel, fateful day when the friends stopped speaking to him for no apparent reason.

As “Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage” begins, the title character is at death’s door because of this sudden rejection. And the author is tossing around phrases such as “bowels of death,” “thick cloud of nothingness” and “dark, stagnant void.” It would help if we knew just what kind of Eden Tsukuru had been cast out of, but no. This book is as short on explanations as it is long on overwrought adolescent emotion.

And either Murakami or his translator, Philip Gabriel, likes to bludgeon each new thought with brutal repetition. So the main thing we know about the self-important five friends is that “like an equilateral pentagon, where all sides are the same length, their group’s formation had to be composed of five people exactly — any more or less wouldn’t do. They believed that this was true.”

The other four all have names that denote colors in Japanese. Next April, when Murakami’s fans lather up about why he deserves a Nobel Prize in Literature, maybe they will cite that as meaningful. But here it is just one more reason for Colorless Tsukuru to feel sorry for himself, because he has lost two male friends, Aka (short and stubborn) and the gung-ho Ao (“Losing is not an option!”), and two female ones, Shiro (tall and slim, with a doll’s look) and Kuro (less beautiful, but smarter).

Shiro also has “strangely eloquent” calves and likes to play Liszt’s “Le Mal du Pays,” meaning “Homesickness,” which floats through this book just as Janacek’s “Sinfonietta” did through Murakami’s previous book, the phantasmagorical doorstop “IQ84.” The Liszt piece is part of his larger “Years of Pilgrimage,” which gives the book the second half of its title.

Once Tsukuru has suffered his high school calamity, he moves on to Tokyo to attend college. The four former friends stay in their hometown, so Tsukuru would appear to have moved on. Drastically. For one thing, in one of the book’s most graphic passages, his body is torn apart by birds with razor-sharp beaks, and his old flesh replaced by … what? “Tsukuru couldn’t fathom what this substance was. He couldn’t accept or reject it. It merely settled on his body as a shadowy swarm, laying an ample amount of shadowy eggs.”

This is the kind of blah surrealism for which Murakami is so beloved by his fans, who will go to any lengths to justify why a minor book such as “Colorless Tsukuru” still has the author’s special je ne sais quoi. The dreaminess of the passage is its stylistic trademark, but there are other, less woozy ways to say that bitter experience toughens Tsukuru into a new man. Thus reconstituted, he even makes a new friend: a beautiful young man named Haida, whose dialogue really deserves to be read in a dorm room at 3 a.m. Haida is a self-proclaimed philosopher in the making, and he sits on the cusp of the earnest and the absurd. “I just want to think deeply about things,” he says. “Contemplate things in a pure, free sort of way. That’s all.” When he and Tsukuru leap into a discussion of the value of human free will, Haida says in all seriousness: “I wish I had an answer for you, but I don’t. Not yet.”

Haida awakens something in Tsukuru, and it’s not his inner Sophocles. Tsukuru begins to have erotic dreams about his old friends and this new one. He is forced to think about his own sexuality. (“The idea that every fold in the depths of his mind had been laid bare left him feeling reduced to being a pathetic worm under a damp rock,” the author writes beguilingly.) It occurs to this lonely wretch that his biggest passion in life may not be for his chosen profession, designing train stations, after all. Then 16 more years go by, apparently uneventfully, before anything else happens.

Enter Sara, a nice, two-dimensional, 38-year-old woman who begins asking Tsukuru the shrinky questions he really needs to answer. In about as sophisticated a plot device as this novel has to offer, Sara says she won’t sleep with Tsukuru until he goes out and finds his old friends and asks them what happened. “I think you have — some kind of unresolved emotional issues,” Sara keenly observes.

“Philosophical observations really suit the way you’re dressed today,” Tsukuru tells her flatteringly, and let us not waste time on the tired subject of how readily Murakami treats women as decorative idiots. The point is that she makes him a little less whiny and kicks off his all-important voyage of discovery.

So what did happen back then? Nothing that would satisfy either a gumshoe or a wisdom seeker. Tsukuru finds the people he’s looking for, and after the most astonishing stalling (“You really don’t know have any idea?” “I really don’t!”) he gets two sets of answers. The first is about why he was so unceremoniously booted. The second is about what his teenage friends grew up to be. Suffice it to say that one sells cars and uses “Viva Las Vegas” as a ringtone, so they’ve all taken their share of wrong turns. They would not have remained friends anyway. That part feels honest.

Less so: a shoehorned moment of wisdom in which Tsukuru is finally able to accept everything that happened to him and grasp “what lies at the root of true harmony.” He also learns to beware of bad elves. As flashes of wisdom go, that’s a very Murakami combination.