Football players get help retiring

Published 4:00 am Saturday, February 4, 2006

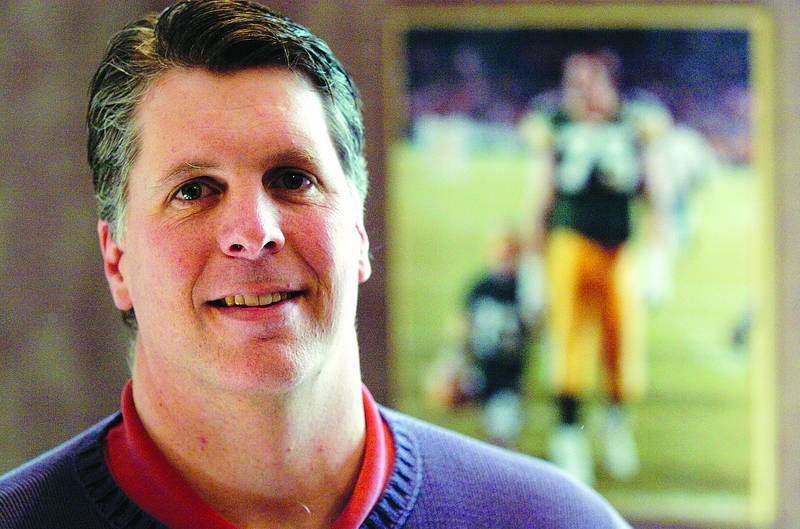

- Former Green Bay Packer Ken Ruettgers now runs a nonprofit organization based in Sisters, which aims at helping NFL players adjust to life after football.

SISTERS – Between his SUV-like frame and the constellation of diamonds adorning the Super Bowl ring on his right hand, it’s not hard to tell that Ken Ruettgers used to play a little football. But after he retired, it was putting that fact behind him that was the challenge for the standout tackle.

For the ex-Green Bay Packers offensive lineman, life in the National Football League was good: The mammoth left tackle was adored by fans as Brett Favre’s protector and well paid for his services. His last contract was a four-year, $8-million deal. In his last season, the Packers won the Super Bowl.

(For the record, Ruettgers will be rooting for the Seattle Seahawks and former coach Mike Holmgren against the Pittsburgh Steelers on Sunday.)

When he had to retire, Ruettgers, who now lives in Sisters with his wife Sheryl and three children, found life after football to be unsatisfying.

”I experienced everything most guys go through: anger and depression and loss of purpose,” Ruettgers said on Wednesday, sitting in a suitably enormous chair in his Sisters office.

Ruettgers’ friend and former boss Don Jacobson remembered visiting Green Bay in the mid-1990s when the football player was at the height of his popularity.

”I’m telling you what, I couldn’t go into a room where he was not just venerated,” Jacobson said.

But after a bad knee forced Ruettgers, now 43, to retire in 1996, all that was over, he said.

”Our heroes are disposable,” said Ruettgers, who was drafted ahead of Jerry Rice in 1985. ”When you’re done, nobody wants you.”

For the past six years, Ruettgers’ mission, through his nonprofit group GamesOver.org, has been helping other retiring athletes make the transition from sports to regular society and dodge the problems that tackle so many ex-players.

For those who might be skeptical about the problems facing professional athletes, Ruettgers rattles off these facts, from his own research: Within two years of retiring, 78 percent of NFL players are divorced, bankrupt or unemployed. And half of players who become divorced do so in the year after they retire.

None of that happened to Ruettgers, who was so responsible that he even earned his master’s degree in business administration during offseasons, but he still found the transition hard.

”I was the poster boy for transition and yet it was very challenging,” Ruettgers said.

After he spent a year hanging around their Green Bay home without any plan for the future, it was Ruettgers’ wife, Sheryl, who told him it was time he got a job.

”She said, ‘You have to go back to work and do something with your life,’ ” Ruettgers said.

Near that time, Sisters-based Multnomah Publishers, which printed Rutgers’ book, ”Home Field Advantage,” offered the ex-lineman an entry-level job in author relations.

Jacobson had no qualms about bringing a retired athlete into his Christian publishing house, he said.

”The only thing I felt apprehensive about is how much I offered to pay him,” said Jacobson, noting it was a tiny fraction of what Ruettgers made as a player.

But Ruettgers – who had never worked in a cubicle, held down a year-round job or worked in a co-ed environment – was nervous.

”I wasn’t sure I could do it,” he said. ”In football you run at a sprinter’s pace; A play for 5 seconds and then a huddle for 30. (My co-workers) were running at more a marathon pace.”

But he settled into the job and the community, volunteering as a line coach at Sisters High School and raising his son and two daughters. His son, Matt, is now a senior at the high school. Katherine is a sophomore and Susan is in eighth grade.

After a few years at Multnomah, Ruettgers decided to pursue an idea that first occurred to him during his playing days – helping other guys make the leap. He put down the seed money for GamesOver himself and in recent years the NFL and NFL Players Association have helped fund its mission, Ruettgers said.

When he started researching the fiscal outlook for an average player, it confirmed what Ruettgers already knew – few players will earn enough to make money worries irrelevant.

The stars can earn enough to be financially secure for life, but the average NFL player isn’t so well off, Ruettgers said. He recites a list of figures from memory: The average NFL career? Three years. Average salary in those years? About $450,000 annually, meaning the average player earns about $1.4 million in his career. Half goes to taxes, leaving $700,000 in real earnings. And in the era of MTV Cribs, even conservative players will spend $80,000 to $100,000 a year. Add it all up and after three years in the league, most guys have about $400,000 in the bank.

When players leave the league, with no job experience outside of football, most opt to try to make it with another team, rather than focus on the future, Ruettgers said.

”Are you gonna go get a job at McDonald’s or are you going to try to get back into the league,” Ruettgers said. ”Obviously the latter.”

By the time they finally focus on getting another job, many players have nearly wiped out their savings, he said.

Through GamesOver, Ruettgers tries to link retiring athletes with peers who have successfully transitioned to the real world. His Web site, gamesover.org, includes advice on finances and relationships, as well as forums where ex-athletes can discuss their unique problems.

Ruettgers said he speaks to about 100 current players every year at conferences and preseason training camps across the country. He’s even planning a retreat for about 15 players this spring at The Lodge at Suttle Lake.

He’s also working on a doctorate, with hopes of doing more research on former athletes and what they can do to succeed. And while he’s far from the nearest NFL franchise, Ruettgers said he’s found the best place to complete his life’s work.

”I couldn’t do this in Arizona or Atlanta any better,” Ruettgers said. ”This is my passion.”

Keith Chu can be reached at 541-504-2336 or at kchu@bendbulletin.com.