The secrets of sourdough

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, March 29, 2016

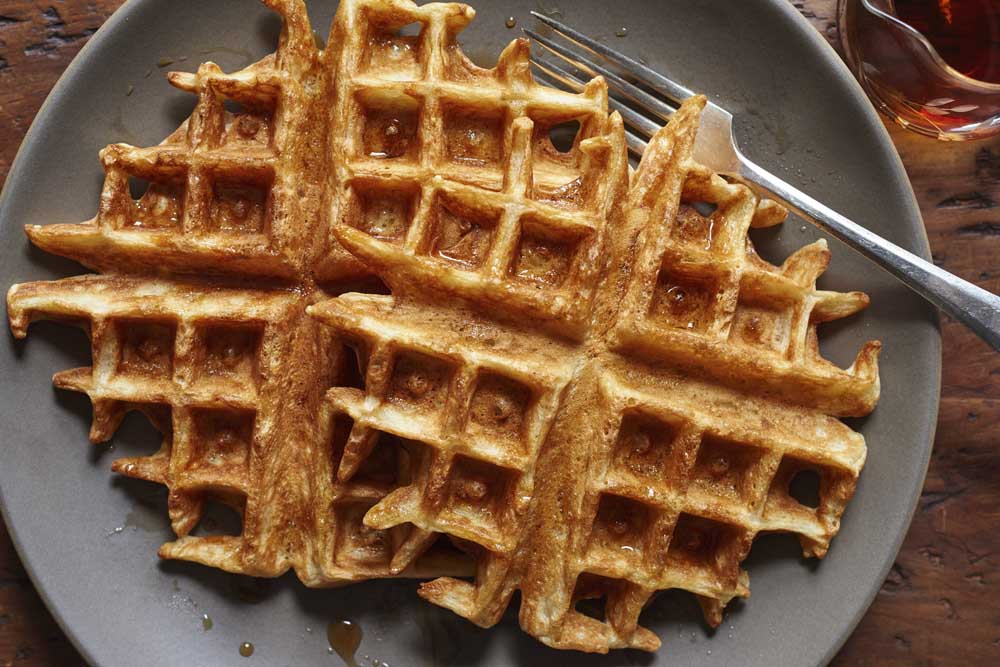

- Melina Hammer / The New York TimesSourdough starter, with its routine feedings, takes more care than many other kitchen projects, but it can be used in various ways. Pizza dough and waffles benefit from its complex tang.

Twenty years ago, after leaving his job as the manager of an Albertsons Market bakery in Twin Falls, Idaho, Rick Hazen found himself missing the taste of fresh bread. He made a sourdough starter using flour and some unprocessed apple juice.

The juice fermented. Wild yeast made an appearance. The starter bloomed. Hazen has been baking with it ever since. “We won’t eat anything else,” said his wife, Lorri.

Trending

Jocelyn Knepler of Bowling Green, Kentucky, was given her sourdough starter by a friend in Midland, Texas, in 1973. “She got it from a woman in Kermit, Texas, who got it from a woman in Golden, Colorado, who started it in 1948,” she said.

Knepler and her starter have since moved together from Texas to Alaska, to Britain, to China and to Kentucky, where she is retired. Her daughter uses the same starter to feed her boys. “It’s a family tradition,” she said.

A sourdough starter comes into your life the way a turtle might: as a pet you maybe didn’t know you wanted until someone hands it to you or you find yourself holding the terrarium after an impulse purchase you couldn’t explain if you tried. You get it or you make it or you buy it, and now you have a sourdough starter. It needs to be fed. It asks to be used.

There are holes in our lives. They are filled for us by circumstance, or we fill them ourselves.

“You do this simple thing,” said the comedian Tom Papa, who has been feeding and using his starter in Los Angeles for more than a year now, after he received it from one of his daughters as a Christmas gift. “And it changes your life.”

‘The proper way’

Trending

Sourdough starter is simply flour and water left to ferment, a medium that supports the wild yeast and lactobacilli that surround us all. Fed with more flour, and more water, a sourdough eventually achieves a kind of symbiosis that helps dough rise, without the use of cultivated yeast. That it delivers a pungent, slightly sour and deeply alluring taste to all that you cook with it is a happy side effect. Taste is not, strictly speaking, the point of sourdough.

“A lot of us think that sourdough is a style of bread,” writer Michael Pollan said in one episode of “Cooked,” his new documentary series on Netflix. “But what sourdough is, is the traditional way that bread was made until only about 100 years ago.”

Pollan can sometimes sound bossy. “Sourdough is the proper way to make bread,” he said in one segment.

It is certainly a simple way to make bread, at least once you have a starter up and going, though the process takes time, because the wild yeast in a sourdough starter is less vigorous than its commercial counterparts. Make bread with a sourdough starter, and the dough rises slowly as the starter ferments and changes, and as it reacts to all manner of factors, like flour type, air temperature, humidity and altitude.

The starter

Start at the top, then. See if you can’t get some starter from someone. Anyone who has one will be glad to part with a cup or so, because to maintain its balance and size, you need to use or discard part of the starter each time you feed it.

Or buy some — sourdough starters have started to show up at farmers markets and on Etsy. The website Cultures for Health sells one. So does King Arthur Flour. Katie Walker, a spokeswoman for the company, said sales of starter are up for the company and on track to be 20 percent higher than last year. “How to Make Your Own Sourdough Starter,” she added, is King Arthur’s top-performing blog post.

So you might try making a starter yourself, combining a cup of water and a cup of flour in a covered bowl and allowing it to sit at room temperature until it begins to bubble and bloom. You can speed the process with grapes, as baker Nancy Silverton advised years ago on a Julia Child television show.

Peter Reinhart, the author of “The Bread Baker’s Apprentice,” uses a few ounces of unsweetened pineapple juice. Add the juice instead of water to the flour and let it sit, he wrote on his blog a few years ago; a few days later your starter should begin to come to life. Nourish its bubbles with more flour, and water.

Storing and feeding

Once you have an active starter, which is to say one that is light and bubbly, with a pleasant yeasty-boozy aroma, a fork appears in the road. Obsessives and frequent bakers keep their starters out on their countertops, using the stuff daily, feeding it daily. Some people name their starters: William Butler Yeast, Herman, Sarah, Sky Pilot, Ms. Tippity, Eleanor, Roxanne.

The rest of us keep sourdough starters in the refrigerator, which slows their metabolism, allowing us to use them, and feed them, less frequently. (We do not name our livestock.)

Still, a starter must be fed. The bakers at King Arthur prescribe a diet of a scant cup of all-purpose flour and 1/2 cup of lukewarm water. Others increase the amount of water, or alter the kind of flour according to their tastes, using rye or whole wheat.

How to use it

Each sourdough is what it is. You can use the starter you pull from your crock before feeding to make a fine overnight sponge, or base, for pancake or waffle batter, or to bring an amazing depth of flavor to pizza dough. It’s a little more complicated than a regular pizza dough, said Anthony Falco, the director of pizza operations at Roberta’s, in Brooklyn. “But, oh boy, the end result is worth it.”

Eventually, you will want to make bread. Recipes for sourdough loaves abound, each seemingly more complicated than the last. Chad Robertson, the baker at Tartine Bakery & Cafe in San Francisco, published a recipe for his sourdough country loaf in the book “Tartine Bread” that ran to 38 pages. It takes about two weeks to complete. You can streamline that recipe a little, but not a lot.

An easier way to start is with an adaptation of the baker Jim Lahey’s storied recipe for no-knead bread, replacing commercial yeast with a little less than 3/4 cup of healthy, well-fed sourdough starter. Give that dough a long, long rise and then plop the proofed dough into a hot, enameled cast-iron pot with a lid. The reward is an incredible loaf within the hour, and you may well find yourself addicted to the smell, the taste and the process.

A growing hobby

Benjamin Seigle, a home baker in Chicago, certainly is. “I take a glob of it,” he said of his starter, “and throw it in the dough,” then he allows it to ferment for a day before baking. He doesn’t have the patience for more, he said, “and my palate isn’t sophisticated enough to notice the difference.” He’s happy with his two loaves a week, he said.

Papa, the comedian, said he bakes three or four times a week. He talked about that one day recently with Joe Rogan, the broadcast host and Ultimate Fighting Champion color commentator, on Rogan’s podcast, “The Joe Rogan Experience.” Mail flooded Papa’s inbox afterward, he said — “dudes, UFC fans” looking to talk baking.

“More people are interested in this than my comedy,” Papa said. He sounded surprised. His whole life up to now has been comedy and hanging out with his family. “Now I think maybe I have a hobby,” he said.